Binge-Watching The Queen's Gambit: '2020', A Review, Part 1

'I play in my head, on the ceiling.'

Green-Pilled

Beth Harmon’s ceiling-chess in The Queen’s Gambit, the Netflix miniseries starring Anya Taylor-Joy, acts as a sort of totalisation of the year ‘2020’. What we see here, and see ourselves seeing, is the young addict (at this stage played by Isla Johnston) reaching an immediate and operatic overdose. In fact, analogous to Tony Soprano’s first panic attack in the pilot episode of The Sopranos, Beth ‘swoons’ onto the floor at the end of the very first episode of The Queen’s Gambit. Tony’s epileptic ‘overdose’ goes down at a family barbeque to the sound of ‘Chi il bel sogno di Doretta’ from Giacomo Puccini’s La rondine. Beth’s takes place while the end of the 1953 film The Robe is playing in the background, its soundtrack in dramatic dialogue with the over-commitment to an addictive cause that will now define.

Beth was meant to be watching the film with her fellow orphans, but magnetised by the large jar of green pills, she breaks and enters into the orphan pharmacology to gouge out on the prize asset, handfuls and pocketfuls of a benzodiazepine sedative that makes her ceiling-play possible.

Among many other facts from 2020, there is this: Anya Taylor-Joy playing a game of chess on a ceiling.

Until now in the story, Beth has stayed relatively okay by the keeping over of the tranquilizers in half-green capsules for bedtime. These had released the night patterns on the screen overhead. Down in the basement with Mr. Shaibel she recognised the game ‘chess’ without thought, in the same way that Dakini script may be understood ‘on sight’:

Buddhists consider the Khando Dayig as one of the thongdrols or ‘liberation upon sight’. In Buddhist tradition, some things are so holy that just the mere sight of them plants seeds in our consciousness that will develop into the cause of our final freedom.

Chess is, as it were, ‘injected’ through the eyes—beyond calculation, and strategy. She sees Mr. Shaibel’s board once in the basement, where she is sent to clean the erasers, and that is enough: ‘I already know some of it from watching.’ That night the viewer themself—objectified as an itself, as we shall see—has its own first sight of Beth’s first sight of the board on the ceiling, in this case empty and without pieces.

As the days progress, we witness a kind of morphogenesis of ‘the game’. Tree shadows metamorphose through the orphanage windows and become spaces on the board, and then, as Beth reads even more quantically, pieces . . . followed in no time at all by the Sicilian defense, Ruy Lopez, Capablanca.

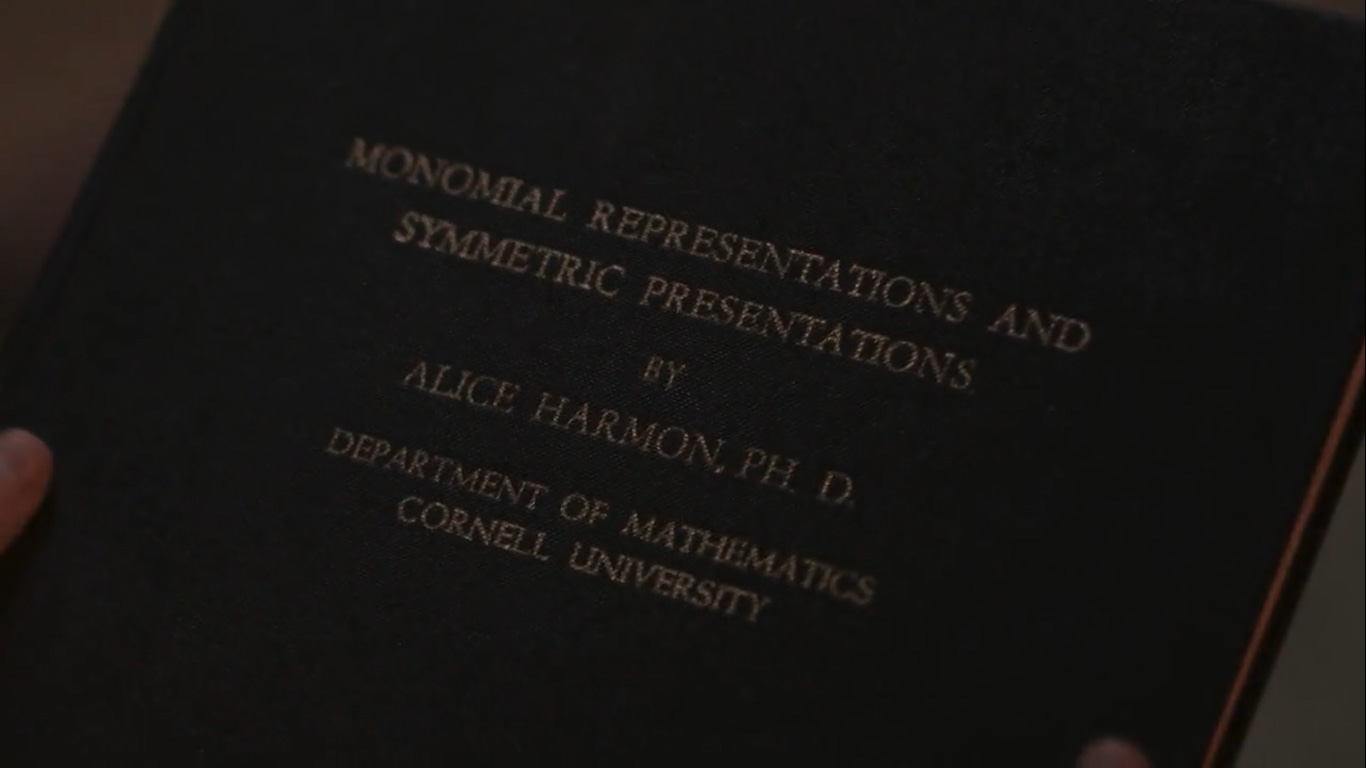

Flashes of information about her mother, who completed a Ph.D on Monomial Representations and Symmetric Presentations, provide an alibi for genius. But genius requires no such alibi, and the Ph.D is part of a mess of superfluous documents in the process of being burned, something Alice Harmon claims is ‘beautiful’.

The thick green Ph.D—never burned so far as we see, and yet presumed lost—turns out to be more than a viewer’s lure. Carlos E. Perez, author of Artificial Intuition and the Deep Learning Playbook, has already written:

Few may have noticed that her natural mother wrote a Group Theoretic Ph.D. dissertation. In one of Harmon’s recollection of her childhood, while her mother burned books. She picked up a green book which was titled Monomial Representations and Symmetric Presentations by Alice Harmon. This reveals her unique innate ability to work with the mathematics of groups and symmetry. It was at this point that I began to wonder if this was a real story of someone I didn’t know about.

We can give the reader a further exclusive and reveal that something like an equivalent of Alice’s thesis seems to exist IRL, a 2003 paper by John N. Bray and Robert T. Curtis called ‘Monomial modular representations and symmetric generation of the Harada–Norton group’. The paper deals with, among other things, ‘a 5-modular monomial representation of 2·HS:2, a double cover of the automorphism group of the Higman–Sims group’, and how this ‘is used to build an infinite semi-direct product P which has HN, the Harada–Norton group, as a “natural” image’. It also mentions how the latter ‘assists us in constructing a 133-dimensional representation of HN over Q(5), which is the smallest degree of a “true” characteristic 0 representation of P’.

It seems that if Beth adopts anything of her chess genius from her mother—which is in one sense moot, given the emergence of the ‘beautiful’ fire—it develops out of an inherited sense of what mathematicians call exceptional Lie Groups. Weirder still, it is this same domain of maths that Kanye and Eric Weinstein once got off on in 2018:

One beautiful definition of such ‘groups’ reads as follows:

In the Lie garden, one also finds five rare flowers, the exceptional algebras: G2, F4, E6, E7 and E8, their rank indicated by the subscripts. In view of Nature’s fascination with unique structures, they merit further study.

These ‘gardens’ may be as unique as we ourselves, that is, of the number of Universal probability. Beth’s five rare flowers are intuited by the viewer itself—a roving, addictive, annual eye—in speeded achievement as a revenge over time, which is what being on-the-internet can feel like. Scan-reading is a form of knowing on-sight, which is why ‘genius’ isn’t quite the name for our witnessing, or for Beth, unless ‘genius’ is now something like the machine, and the way it reads.

A palm full of hoarded green pills seems to unlock something more than purely abstract ‘ceiling chess’ each evening, hence the sense of totalisation. This is abstract gaming born of equally abstract triumph over biotic trauma (‘close your eyes’), the determination (in all senses) to know just what the dimensions are without looking.

By the same piece, reading chess strategy books under the desk during a teacher’s reading aloud of Stevie Smith’s ‘Not Waving but Drowning’ signifies not ‘being much too far out all my life’ for the hero, but the quantic determination—again—to know what comes of that.

Skip Intro

In November 2012 the film critic David Thomson discussed Homeland in an interview with Greil Marcus for The Los Angeles Review of Books. Thomson was more than enamoured. Riffing on a metaphor introduced by Marcus, he pinpoints the blatant transference-addiction mode of extended TV shows, especially perhaps with regard to the fractured intensity of Homeland (four quartets broken up over the adverts) and its exponential televisual Zeigarnik Effect (‘cliffhanger’-effects across a whole season, and between). The addictiveness of contemporary internet TV stands in a kind of direct and accelerating proportion to a certain end of the world:

It was a wonderful suspense machine. You used that image just now about putting the needle in yourself, and the sort of self-abusive, self-destructive element in our culture is a part of all these things. I think drug-taking in a way is an equivalent, or an extension, of the fantasizing in movies. It’s part of the encouragement to seek a very private, calm world. That notion that if the world is going to end, we’ll all need a drug. I am not a drug-taker, but I am a medication-taker, and it changed my life. I think more and more our loneliness is being assuaged by addictions of one kind or another and it will be a big part of the end of the world.

This qualification of serial-watching as a ‘big part of the end of the world’ has been more than proven by now. Spending some of Xmas 2020 bingeing through The Queen’s Gambit, Thomson’s realisation came back to me as I literally felt, once again, the syringe going in. The connection in this case is more than superficial. Not only is Taylor-Joy’s chess prodigy a pill addict and alcoholic, but the process of watching her across seven episodes is itself one of civilizational abandon.

That addiction is embedded into the watching frame itself, and not merely the narrative surround, is shown in the way the ‘next episode’ feature now works on Netflix, carrying the viewer onwards in a wave of obliterated will. One is, as it were, calculated to binge. One is enumerated in advance by irreversible auto-play as the addict watcher of serial internet television. One is exposed to the pure cerebral slice and drop, appealed to, by and at the end of the world.

Watching is in fact increasingly caught up in this tuning of addictive mechanisms by end of the world frequencies. In Covidian game-space, the reliance on finalist structures—a type of habitual architecture we create out of duration itself—increases ‘as if on a daily basis’. As finitude rallies, at a personal and global level, we turn to longue durée film as a drug and fix. As I watched The Queen’s Gambit, which I was doing partly because my parents and sister had already watched and recommended it, and partly because they had hinted at their own addictive responses, I found myself empathizing not only with Harmon and her medicated fugues, but with my own family in their imagined empathizing with her.

Addiction is not condemned or analysed as such in The Queen’s Gambit; rather, it is shown to be intrinsic, intelligible, and part of Beth’s own sense of emotional achievement and gravity—or rather, lack of gravity; her modus operandi after all being anti-grav.

When flashbacks show us the ways in which the young Beth witnesses and was part of the car crash that killed her addict mother, we understand at the level of meta-empathy her plight and her momentum as being the same thing. She has no choice but to be this type of chess genius, in this way, at this time. The viewer, in a parallelism, is caught in the same positive embrace of compromise and durational addiction. There where time shortens and threatens to cut out entirely, The Queen’s Gambit provides the serial-checkmate of spreading, extending and making thick the meanwhile that remains. The impersonal genius of such ‘TV’ is the endgaming of extreme temporal fragility.

Insofar as Beth is defined by her car crash with her mother, so my viewing experience of The Queen’s Gambit was reliant on my own family’s being witness to Beth’s car crash, and on their own functional addictions and viewing habits being translated into my own—as if in an empty genealogical mainlining.

The Brain of Netflix

When Catherine Malabou writes in ‘The Brain of History’ about how the human defined as ‘anthropos’ in the anthropocene may be considered a geological force, she also describes this ‘anthropos’ in terms of the ‘addicted brain’. She reads Daniel Lord Smail’s On Deep History and the Brain to show how the brain usually reacts to its environment with at least some degree of addictive patterning, and how this applies too in the case of a historical epoch as apparently unique as the anthropocene. Addiction takes place as historical adaption at bridge moments in history, so that ‘new addictive processes and chemical bodily state modulations’ are called up to cope with the greatest amounts of change.

To suggest that the brain in and as ‘anthropos’ is living through an exposure to the thought and feeling of extinction (climate change, Covid, the ‘game’ spreading, and so on) like never before would therefore be to suggest that the brain is producing and working through new addictions, that is to say, through new types and degrees of addiction. This leads Malabou to make three propositions, all of them determining something like a positive conception of addiction:

How can we extend these remarks to the current situation ? First, they lead us to admit that only new addictions will help us to lessen the effects of climate change (eating differently, travelling differently, dressing differently . . . ). Addictive processes have for a great part caused the Anthropocene, and only new addictions will be able to partly counter them. Second, they force us to elaborate a renewed concept of the addicted subject, of suspended consciousness and intermittent freedom. Third, they allow us to argue here that the neutrality [Dipesh] Chakrabarty talks about is not conceivable outside a new psychotropy, a mental and psychic experience of the disaffection of experience. Such a psychotropy would precisely fill the gap between the transcendental structure of the geological dimension of the human and the practical disaffection of historical reflexivity. The man of the Anthropocene cannot but become addicted to its own indifference. Addicted to the concept it has become. And that happens in the brain

Man here is it, not he, she, or even they. Man, as addicted and addictive anthropos, experiences itself going through new addictions and experiences itself as indifferent to the extinctive processes of which it is part. And yet, says Malabou, it is only in this indifference, which may express itself in the form of durational watching, that man can be expected to get used to and take time for its newer definition.

In this sense, it is insufficient to say that watching The Queen’s Gambit is addictive. Rather, ‘binge-watching’ is defined as being a witness to one’s own addiction and indifference, and finding this witnessing itself to be productively pleasurable and meaningful. As part of the same argument, the distinctive singularity of Taylor-Joy’s face (the size of her eyes, the shape of the mouth, and so on) takes on an added significance different to the conventional one defined by the male gaze or by a fascination with the movie starlet’s quirky and beautiful features and qualities. If Taylor-Joy’s face is conceived as beautiful in some sense, this is surely now tied to man’s gaze as witnessing brain. The more we see her face, the more it (the brain, anthropos, etc) has the illusion of getting used to it, working through its suggested expressions and features, and even getting used by it. Extinction itself gets used, worn down, seen in and as the face of a star, and in and as the face and experience of geologic addiction.

Covid Diaries

The ties here between family, durationality, and addiction are, as is obvious now, unexpectedly meaningful. From accounts of watching TV series in this century we can expect only confirmations of these linkages and their deep time nature. Right in the moment of the first flush of Covidian confessionals, in a Thomson film diary in the Los Angeles Times from April 2020, we find reflections on ‘box sets’, viewing with one’s spouse, and on how the Criterion channel is ‘the Gideon Bible of this survivalist season’. Thomson quickly acknowledges in this description of a new Bible that durational viewing during Covid is nothing less than a way of staying alive—disaster viewing is disaster prepping. We build our redoubts out of the longueurs of our lockdown seeing:

Tuesday, March 31

On March 27, my wife, Lucy, and I began on the third season of Ozark. We had been waiting for it for months, after we did seasons 1 and 2, two episodes a night, denying ourselves the real wildness of bingeing through the complete show in twenty hours. We loved it, and watching it together deepened our relationship. Surely that had something to do with its poker-faced account of a marriage coming apart.

Expectation, shared silence in viewing, killing time, timing out, winning out over time, adapting through and as time, flexing through and as indifference, mourning, unmourning, demourning: all of these are wired together in the early Covidian phase of viewing and witnessing. In this setting, the car of Godard’s Pierrot le fou, a film which Thomson and his wife rewatch, becomes the car in which they drive around California in lockdown:

The light, the space. With our son Zachary we drive to Point Reyes. It’s the three of us (everyday companions) in the car, our spare room. There is some traffic still; it is California. The day is nearly summer in its warmth, with a wind whipping the sea into white crests. We just drive around—walking has been banned—studying the herds of black cattle and poppies, pale yellow at their tips darkening into egg-yolk at their center. They seem photographed by Coutard. Neither the poppies nor the cattle know what’s going on in the Trump press conferences. Their good fortune.

In the end, the diary will admit, it’s either movies or extinction. If the movies don’t hold up, there’ll be nothing left to protect us at all. Fantasy completely unplugged. Man, unable to bear much reality, planted now firmly in reality, and yet without bearing.

So in alarm I’m going straight to the surefire bliss of Jacques Demy—Lola, Bay of Angels, Umbrellas of Cherbourg. God help us if they don’t stand up. There’s only white bean soup after that—or starting Ozark again.

But, of course, when T.S. Elliott says, to be precise, ‘humankind cannot bear very much reality’, he did not necessarily mean ‘man’ and ‘it’ in the sense Malabou provides for these words. Where humankind cannot bear very much reality, and so turns to addictions as refuge and cocooning, Man as anthropos may be imagined to actively bear very much reality and so has to resort to addiction and to addictive witnessing as itself a form of getting used to and getting used to being used by its own carapace. Man bears very much reality in its Covidian phase of transition, at the point of being cut off, precisely because its momentum is not its own. Its speed comes from before it, from a car crash, a family, a non-optional ‘next episode’ button.

Rewatchability

In the early evening, before finishing The Queen’s Gambit, I rewatched No Country For Old Men alone with my dad. Alone, because my mum volunteered to go through and do her own watching in the bedroom so that my dad and I could spend time watching together, something we did a great of in my teens too, which must have, as Thomson says, ‘deepened our relationship’. No Country For Old Men is a film we have seen before, and even already rewatched together. It is a film both of us find to be what we call ‘prefect’, and so we can watch it in complete agreement and with no need of doubt or worry about the other’s reaction. Such a shared view, such a noncritical consent, is no doubt part of what Thomson means about viewing season 3 of Ozark with his wife as a ‘deepening’. Such a viewing orientates a space for pure time, unmediated by the lures of needing to judge and to assess. If the film or series in question is being watched for the first time, there may be interruption by critique, by the question of choice, even by the moment of turning over to something better—in the multiple-viewer setting of the family, this turning over is translated as the need to find ‘something we can all watch’.

Just as genealogy and addiction are linked and develop through motifs of pregivenness shared with the viewer in The Queen’s Gambit, so in No Country For Old Men the whole of the film pivots on whether we believe Anton Chigurh (played by Javier Bardem) is right to affirm the arbitrary nature of his killing spree in terms of a coin toss and to attribute this chanciness to his own appearance on earth as Man as just another gambit. In a key moment of dialogue with Carla Jean (played by Kelly McDonald) at the very end of the film, Anton’s coin toss philosophy is challenged when Carla refuses to play along.

Call it.

No.

I ain’t gonna call it.

Call it.

The coin don’t have no say. It’s just you.

Well, I got here the same way the coin did.

Just when Carla seems to have trumped Anton by playing the card of psychologism—it’s not the blind pulsion of laws that determine the killing spree, but Anton himself and his aberrant personality—Anton, who seems never surprised by anything anyone says to him, simply sighs and points out that he himself has the same nature as the coin. The irreversible nature of things is not separate from Anton as what Malabou calls ‘man’ precisely because Anton—whose name encrypts ‘Anthropocene’ in an all too obvious way—qua man is pregiven as stone, as geology, as self-indifference. Playing on similar themes elsewhere in the film, Anton at one point asks a character about to be killed by him (it),

If you the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?

This is a brutal, but necessary, comment on what Paul de Man would call the suicidal epistemology of tropes. If all human tropological intercourse is rule-bound to some extent, then the rules that bring Man to the moment of self-extinction would themselves mean nothing in that very moment. At such a juncture, meaning is only contained in the supplement, which is to say the experience in which Man reads itself as it, as an indifferent geologic function and functioning addiction, that is to say what Tom Cohen has called ‘addictogenesis’. Anton comes from the same place as the coin because Anton as ‘it’ is the coin. Both of these its are thrown into irreversible being-together, into the killing air of Covidian mitsein, and the refusal of this statement is clearly a repeat of the rule you followed and which brought you to this.

Is this what my father and I responded to in the film, and what we could have only agreed on? In other words, the enjoyment of No Country For Old Men would have had a lot to with it stating without question what can’t be argued with—for ‘man’ as Anthropocene viewing brain.

Mankind can bear too much reality, but only in addiction may see the lack of figure on the ceiling. It can bear sheer externality, but only in addiction as the plastic concept of serial viewing.

There are very many other ways in which ‘2020’ might be defined as being a notation of this insight that addictogenesis brings with it a positive, or at least thinkable, content. I will point to a couple quickly here. For example, Matt Taibbi’s 2020 book Hate Inc. is a detailed description of the use of what he calls ‘rhetorical addictions’ in the MSM (main stream media). He writes:

This is not reporting. It’s a marketing process designed to create rhetorical addictions and shut unhelpfully non-consumerist doors in your mind. This creates more than just pockets of political rancor. It creates masses of media consumers who’ve been trained to see in only one direction, as if they had been pulled through history on a railroad track, with heads fastened in blinders, looking only one way.

On a similar addiction riff, the point of David Fincher’s latest, Mank, a film The Guardian predictably described as ‘addictive’, is that addiction itself helped create Citizen Kane, a work of art known—debatably of course—as the greatest film ever. Screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz’s openly avowed alcoholism is the condition of possibility for Welles’ greatest moment of ‘genius’, but this throws ‘genius’ itself into a type of paralysis, which the film echoes (Citizen Kane, in my view, is one of the least rewatchable films). As Malabou writes,

How can we feel genuinely responsible for what we have done to the earth if such a deed is the result of an addicted and addictive slumber of responsibility itself ? It seems impossible to produce a genuine awareness of addiction (awareness of addiction is always an addicted form of awareness). Only the setting of new addictions can help breaking old ones.

And like stated, Anthropos—it—can only watch itself, on and on. Like the shared view of a TikTok #duet: