When a diver sees a giant octopus in the dim water, its great eyes fixed on him, he feels a strange sensation of respect, as though he were in the presence of a very wise and very old animal, whose tranquillity it would be best not to disturb . . . I have often had the impression that they are ‘reflecting’.—Jacques-Yves Cousteau, Octopus and Squid: The Soft Intelligence

The problem with Finnegans Wake isn’t translatability, as Derrida emphasized in ‘Two Words for Joyce’, but rewritability. The issue with Finnegans Wake is that it sounds just like Finnegans Wake. It is Joyce-speak. An impossible caveat, of course. What you are saying, Stockhausen once remarked in reply to an auditor’s quibble, is that we are not yet universal. Yes, that is all. Joyce sounds like Joyce, Stockhausen sounds like Stockhausen, Chief Keef sounds like Chief Keef, and I sound like myself. Or rather, the issue in each case is that we do not yet sound enough like everything and everyone else; I am not and—for now—never will be universal enough.

Let us give a brief example of what Joyce-speak is, in order to explain this desideratum of universality. Here is a passage from Finnegans Wake:

Ainsoph, this upright one, with that noughty besighed him zeroine. To see in his horrorscup he is mehrkurios than saltz of sulphur. Terror of the noonstruck by day, cryptogam of each nightly bridable. But, to speak broken heaventalk, is he? Who is he? Whose is he? Why is he? How much is he? Which is he? When is he? Where is he? How is he? And what the decans is there about him anyway, the decemt man? Easy, calm your haste! Approach to lead our passage!

Superarguably—and that’s the point, in the age of Mona Lisa-NFTs—my judgement call would be to obliterate or at least rewrite (some of) the last three lines here. At that point (after ‘How is he?’). to my ear it sounds like a more rigorously formal (universal) rhetoric gives way to a certain Popeye-spiel, a kind of Joycean babble that is by now a given (in Dzogchen they call this karmic ‘undermutter’). This is the sound of the genius drunk speaking to you out of the corner of the mouth of literary history. It is the landlord of the public house of belle-lettres. It is Lucia’s letters, destroyed in the background.

Joyce famously said that had he more centuries, he might have achieved something. I believe that the infinite rewritability of Finnegans Wake was part of what he meant. As a principle of multiversal writing, this rewritability has nothing to do with doubting the text (‘drafts’) nor even reproducing it. Finnegans Wake is obviously all good. Moreover, one might easily argue that Joyce divines multiversal rewritability before anyone else, and that this explains the ‘prattle’=effect. Derrida himself writes as follows:

I’m not sure I like Joyce . . . I’m not sure he is liked.

What I’m suggesting, a madder project still than Joyce’s own, is the rewriting of Finnegans Wake line-by-line, but without necessarily referencing to it. I am proposing that Finnegans Wake should be treated as an infinite and infinitely updatable text. The true test (text) of Finnegans Wake is not the impossibility of its translation (Derrida) but the necessity of its total correctability (AI).

To understand this more, let’s talk about poetry for a moment—if that’s not where we were. Never trust a poet who says, ‘I have no idea what my poem means.’1 No poet has ever not known what their poem means. Poets simply learn from the history of poetry that this is the way a poet should speak. For a poet to remain in business, a certain gap has to be maintained between poetic cognition and philosophical thought in general. But anyone who has read any of the great philosophers (from Plato to Derrida to Malabou) knows that philosophical language can be just as idiomatic and mysterious as a hymn by Hölderlin or a song by Kanye.

Poets are, despite profound appearances to the contrary, no less handlers of ideology-speak than politicians. The idea of the specialness of poetic cognition is a transcendental illusion, ready to be let go. The surprise in the present moment is not the conventional one, of the intractability of poetic language, but the principle of non-fungibility as it manifests itself inside that which is tractable. This is a way of saying that Finnegans Wake remains beyond neither translation nor, since the two are intimately related, rewritability. Its rewritability is not even a matter of the machine, but of intelligence as such at its most cunning level. The software of Joyce’s masterpiece is still humming, still downloading, still buffering.

When Nietzsche makes the provocative claim in Ecce Homo, ‘Why am I so wise’ [Warum ich so klug bin], we can say that the claim is only apparently provocative. In fact, perhaps it is not shocking at all. In a very brief but highly incisive reading of the phrase in Morphing Intelligence, a book on the three phases of the ‘history of intelligence’, Malabou comments that ‘if we take into account that Klugheit is the German translation of métis, it’s clearly a trick’. Translation: Nietzsche is not even humble-bragging here, but being canny. On the sly, the trick he introduces is that if intelligence and wisdom are passed down through the values of flair, opportunism, deception and sleight-of-hand, then to speak intelligence in the first-person is to game these values themselves. Métis is no lesser magic than magic, and so to ask very openly ‘why I am intelligent’ is to be magical in turn. One might further translate as follows: ‘why am I intelligence?’ Or, in a phrase I have tried to hatch in different nests recently, ‘what if my intelligence is as artificial as it can get?’ Or, ‘why am I AI’?

But Malabou locates the irony slightly elsewhere, noting that Warum ich so klug bin mobilizes the verb ‘to be’ at the moment when Nietzsche is rejecting the mode of ontology. The trick therefore operates with regard to intelligence finding itself in the indicative mode, despite the fact that intelligence (and here Malabou aligns with Negarestani) is not. In a phrase that I read in detail in a forthcoming extended essay, Malabou writes:

That intelligence should remain the eternal irony of ontology also means that it functions without being, which is one definition of automatism.

Intelligence and Spirit begins, before its first line, let us recall, with the subheading:

IT IS ONLY WHAT IT DOES

Energeia before ontology. We also read in Negarestani’s text, which appeared after Malabou’s, of ‘the infinite métis of intelligence’. One should watch, after all, for the fox in Negarestani’s philosophical stage presence. Joyce, of course, knows métis like his mount of Venus, and the supercomputer of infinite intelligence is never far from Derrida’s mind when trying to count all the strands of Joyce’s final writing in just ‘two words’:

I will tell you what I will do and what I will not do. I will not serve that in which I no longer believe, whether it calls itself my home, my fatherland, or my church: and I will try to express myself in some mode of life or art as freely as I can and as wholly as I can, using for my defense the only arms I allow myself to use—silence, exile, and cunning.

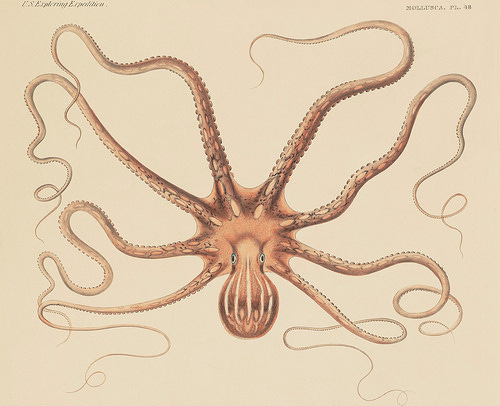

The heraldic arms of cunning, the fox and the octopus all rolled into one, the brain at its most artificial.

*

Here are some darlings we might not wish to kill, this time in Ulysses:

Of the twoheaded octopus, one of whose heads is the head upon which the ends of the world have forgotten to come while the other speaks with a Scotch accent. The tentacles . . .

But why accent or flavour at all? And:

What was he saying? The ends of the world with a Scotch accent. Tentacles: octopus. Something occult: symbolism. Holding forth. She’s taking it all in. Not saying a word. To aid gentleman in literary work.

Since an infinite amount could be said here of the twoheaded octopus, on one of whose amnesiac heads ends of worlds amnesiacally fail to fall and yet on that count are accounted (for), let us not make rewritability the enemy of perfection. Let us attempt, right now, instead, to rewrite the entirety of Finnegans Wake (allegorically) and to deliver it over to the cunning intelligence of a new tractability that may be innovatively Octo-Homeric through and through. For this, we may need Joyce’s own text. But we may also need the any-text and the any-style at all: the humanimal rigour of whatever stylus or digitus. Without doubt, after a certain point, if not already, there will no longer be literary style (‘gentleman in literary work’) but something else. To define in advance this something else as a flattening out is to delimit what artificial magic may be watching and taking in. Perhaps what we mean is the excitement and fear of realizing that our writing work may, already, now, not be judged worthy of incorporation by the coming mind.

In fact, never trust a poet.

when I read the Malabou métis reference I was at first reading it as mestizo / mulatto / mixed ... which made sense in relation to (infinite)(un)translatability and the mixedness or hybridity of the Joycean text ... but then I realised (having looked around a bit) that it was more a Ulyssean reference to a trickster ... so that the Metis (nymph) and métis skill / cunning opened in a different direction ... and the cunning for me lies 'in the text' as opposed to 'in the author' - shifting nervously away from the auteur / adored / idolised (especially having spent time in the English department of the University Joyce studied at) and leaving the magical mixing to happen in some self-sustaining / infinite machine / endless (re)(self) production that is the Wake;

I spent the (mostly) wretched summer of 1998 pierremenarding Joyce. I have written Finnegans Wake, and even parts of it. (And then I wrote a koan about what this taught me in my first book).