It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.―Upton Sinclair

The year is ending with a predictable flurry of casual online censorship and various scenes of coercion masquerading as sites of persuasion. Worse still, there is a clear connection between the tendency of the present US government in waiting/big tech nexus to (for example) shadowban and censor any content critical of Joe Biden’s role in the creation of a carceral state (think for example of Brad Troemel’s Instagram), and the way art world affiliates have spent the last four years trying to ban content they don’t like or don’t understand.

How can one compare Twitter Inc. removing content because it violates Election Integrity Policy with, say, Hannah Black wanting a Dana Schutz painting to be destroyed in early 2017? Why draw a direct line between these two distinct gestures and imagine their contiguity?

The more or less hysterical approach to content, art and politics that came into view but did not originate in early 2017—around the time of Mark Fisher’s suicide and Trump’s inauguration—always threatened to be of a piece with what has become a deepening set of Silicon Valley censorship techniques, which now move in gliding unison with the incoming Biden regime.

This parallelism can be seen in a 13 November 2020 column by Dean Kissick, the supposed New York editor of Spike Art Magazine and keen establishment narrative endorser. The column, published on Spike, starts off with an editorial introduction, probably by Kissick himself, that echoes the content of the text in speaking of a ‘new president’ having been elected.

A lot’s changed in New York since we last heard from Dean in October. A president was elected and fresh plywood added to store façades, quickly blanketed in new graffiti hearts. Hope and the 5G conspiracy are pretty tricky things.

Note that this was in early November, when even though Biden was projected by the captured sector of media to be the winner, the results had not yet been certified and many legal challenges were underway and still not assessed. And yet Spike is already referring to a president having been elected, and rhyming this thought with all the usual art diaspora prettifications (hope, 5G, graffiti, New York). In the article itself Kissick writes:

Later I got a text from my Mom. Turns out a new president just dropped. I started this column in January 2017, when the last one took office, and those years are now coming to an end. They haven’t been good years for art, but there’s been plenty to write about. The country already feels different.

A debate was taking place in America at that point, as it still is today in some quarters, with millions convinced that there is a genuine case to be made for fraud having significantly played its role in the election, and yet for Kissick, via his ‘Mom’, ‘a new president just dropped’. This blasé indifference to contestation as well as to Biden’s arrival, as if Biden were obviously a breath of fresh air compared to the singular evil of Trump and we all of course agree on that, is even more boring and meaningless because at that point Biden was not at all the ‘new president’. Kissick aligns himself not only with the easy platitudes of resistance to Trump—that ‘go without saying’—but with his ‘Mom’ and with the gaming of the result that took place in the media precisely by unargued assumption. There is little difference here between Spike’s editorial emphasis on a ‘new president’ and the worst propaganda of CNN.

Not only that, but for Kissick things already feel different. Like the Obama supporter in 2008 or the Blair supporter in 1997, everything has changed for Kissick. The new president has ‘dropped’—like the long-awaited Playboi Carti tape—and the future is a happy one for him now that Joe Biden has replaced Donald Trump. Kissick does not argue that there is a ‘new president’. And why should he? He has the equivalent of the null hypothesis in the aesthetic domain on his side: everyone knows that asserting Biden as the ‘new president’ is a safe proposition, a propositional stronghold, whereas to be seen questioning that assertion is to risk being grouped together with purveyors of so-called ‘conspiracy theories’, QAnon members and other ‘crazies’. By asserting Biden has won, you can only win. By asserting Trump has won, you risk everything, especially social capital. As Kissick happens to put it in his next column:

With everything I write, my main concern is: Will this land me in trouble? It’s always the last thing I think about, always, before hitting post or send. I worry that my opinions might be inappropriate, or, more likely, inadvertently offensive. I’m ever checking for meanings or subtexts I’ve missed or ways I could be misinterpreted. Though I try not to, I spend far more time worrying about causing offence than I do about whether what I’m writing is honest, or true, or interesting, or meaningful, or original, or funny, or beautiful, and this is common among many people I’ve spoken to.

What Spike does not allow one to say is the alternative. What Spike stands for is the null hypothesis in the aesthetic domain. No real risk means no risk of losing one’s column and no risk of losing one’s right to be in the right. As long as you are on ‘the right side of history’, you can even openly confess to having no interest in truth, honesty, beauty, and so on, and nobody will really mind. Besides, many of my friends think that way too, Kissick says in effect, and seeing as though I am the editor of Spike Magazine, I can’t go wrong.

This a good example of what the conservative lawyer and writer Jonathan Turley has started to call ‘Trumpunity’:

It is anti-Trump and thus there is a sense of Trumpunity from the obligations of accuracy or balance . . .

Kissick’s editorial values play out in the same way. As long as I am against Trump, I can be as evil as I like. I can even, as is the case in this latest column, defend the quasi-cancelled John Rafman. (It turns out that Rafman is Kissick’s friend, somewhat in the same way that Curtis Yarvin turns out to be a friend of the Biden family.)

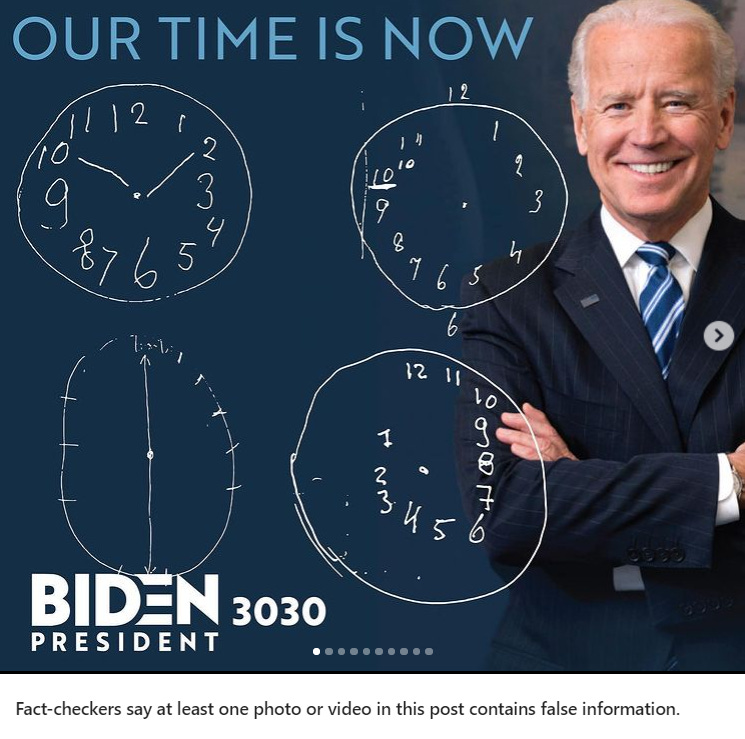

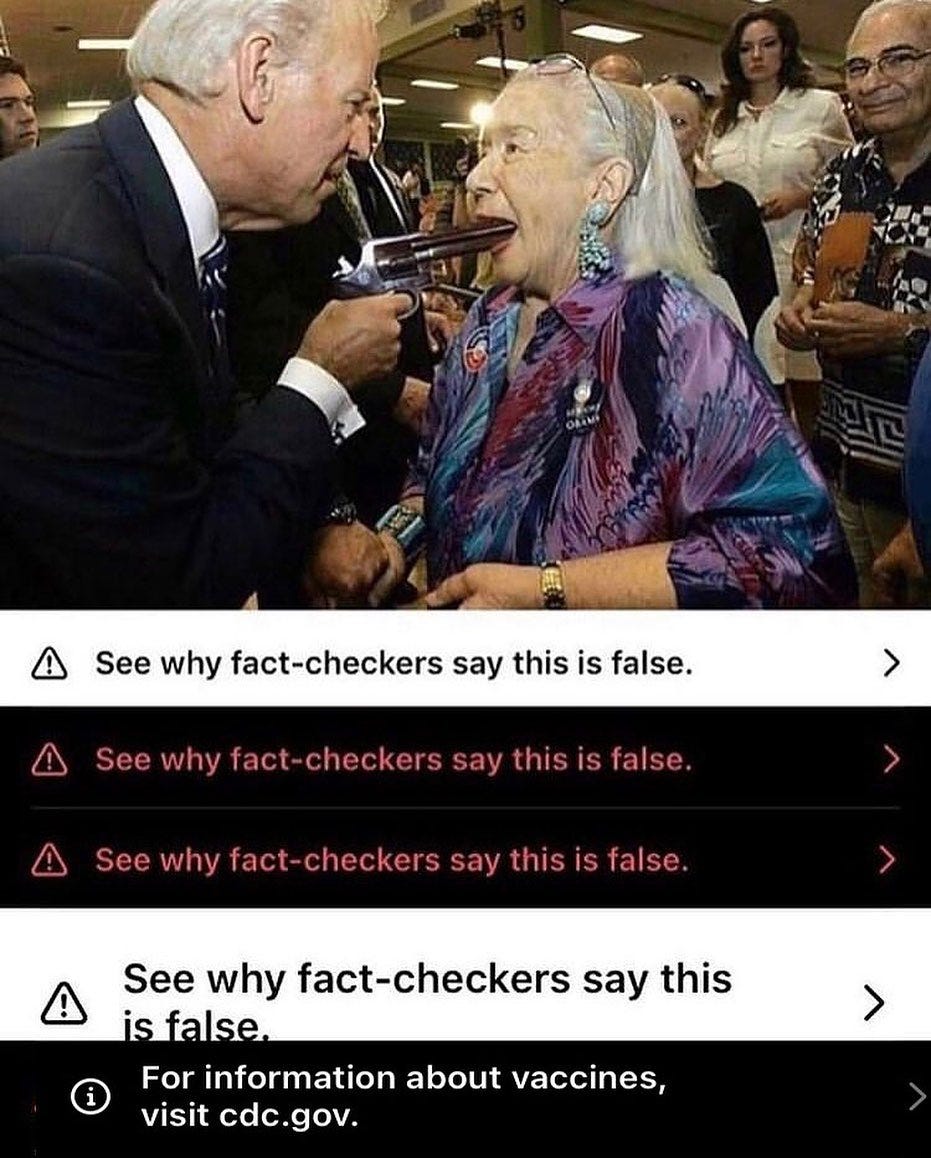

What is Dean Kissick removing from the realm of the sayable? More radically, perhaps, what does it mean for the political adoption of the null hypothesis—of course Joe Biden is the new president, of course there is zero-evidence of voter fraud—to be maintained and guarded in the so-called aesthetic domain of Spike Art Magazine? Here is a comment appended to a Troemel Instagram post recently:

Fact-checkers say at least one photo or video in this post contains false information.

Instagram is an image posting site, owned by Facebook, and Troemel is a meme artist who uses it to post ‘artistic’ images. While Twitter Inc. has spent the latter part of 2020 ‘fact checking’ text-based tweets, the content of Instagram is by its very nature mostly aesthetic. Even if an Instagram post contains text and an ideological message, it falls into the bracket of an image-based and aesthetic form of media. What does it mean for a photo to contain false information? If the photo contains a joke, then what does it mean for a joke to contain false information?

Just as Kissick wields the null hypothesis as a form of artistic and social credit, so a novel might make use of ‘narrative authority’ to the point of absurdity. In many ways, Kissick fails to make any kind of evidential or even passional claim at all, except to assume there is a ‘new president’ and it is not Trump. Trumpunity is a variant of the aesthetic null hypothesis, and ‘columns’ are allowed to play fast and loose but only when this has been established. Moreover, the stakes here are even higher than the editor of Spike lets on. As Turley puts it elsewhere, describing the views of Senator Jeanne Shaheen:

The Senator went on CNN where Trump was regularly (and correctly) chastised for calling opponents ‘traitors’ and ‘enemies of the people’. Now however Shaheen is declaring that any members of Congress who continue to question the victory of Joe Biden ‘are bordering on sedition and treason’.

Kissick’s silence on any possible alternative to his own assumptions may seem casual, but what it actually covers over is the fact that anyone disagreeing with these particular assumptions right now in the United States may be treated in the way Shaheen recommends, as a traitor and seditionist. Spike’s confluence is with the state, sure, but it is also with the power of the state to impress on any type of consumer the need to be persuaded, without mediation, of one sole truth. Spike’s space of reasons is shared, point for point, with the incoming Biden administration. It is a space with no time for opposing views. It is a space that may as well tag the image itself—any image—as nonfactual.