First Memory

I want to write it so simply.

I’ve heard many people say they miss the early weeks of the first lockdown. I want to recall this. To record it, maybe even to keep the memory of this idea.

To put it as simply as possible, for me it was a time when mortality felt very raw.

I remember being convinced with great clarity that extinction had begun, that a process I had waited and watched for and knew to be already under way had at last arrived and now was it.

When our civilizational body begins to die, it will first of all catch a cold. Total breakdown is then imminent.

This is what I felt I knew at the time. I still feel I know it now. I realize, in the present, that I have no idea whether I have a right to hope I am wrong.

To hope I am wrong with regard to such a singular case, does that mean hoping that a death that has to happen to a body for the body to be a body is not there? How could I hope such a thing? Would that be hope at all?

Running Into Death

I want to write this so, so simply. Am I succeeding?

My Rinpoche says that in the fully enlightened state we go to death as we run into the arms of a lover, this time anticipating the best sex in the world, sex we could never have imagined we would have.

We embrace it, we get hot for it, we love the end itself, and the ending itself. Who would have thought?!

Early on in lockdown the theme of her transmissions was stated as impermanence, and I felt I had never encountered this word or concept before.

My Rinpoche’s own Tibetan Teacher had died in Tibet just as Covid was beginning to spread in China in December of 2019. He bestowed her with one mission: the betterment of Dzogchen around the world.

Without the co-incidence of Covid-19, in other words, there would have been no betterment of Dzogchen as she sees it.

Purity is Pure

Among her perfected efforts, she has proposed new translations of primal Tibetan and Sanskrit terms. Emptiness, for instance, has become purity.

There is no emptiness at all, only a purity pure of everything. It’s grown to mean just that for me in a way I can’t add many words to.

The gifts are innumerable of what happened to me at that time, but it strikes me again and again that Covid was the opportunity and confirmation of a profound teaching of impermanence. Without Covid, we would have no new translation of what ‘impermanence’ actually is. It is as if we would not know the word at all.

This is the meaning of the death of the Guru. As my Rinpoche’s Teacher died, so then she was emboldened to go all the way with the teaching that is seen as the Golden Egg, even among the rich Buddhist Lineage that takes in at different points the immensity of Chinese history.

Covid was the occasion for the betterment, which is to say universalization of Dzogchen, of the Golden Egg, the full rainbow. So we could do worse here, and now, a year later, than to listen for the delicacy and timelessness of this balancing act.

No matter the indestructible vehicle we each find it in.

Transference

Am I writing this simply, or even more simply than the simple? I trust it is as simple as can be.

Everything explained here is at the beginning of what it might be, and yet since there is only the origin-less and the beginning-less beginning, there is no need to explain the reservoirs of what would be different in my praxis had I already taken more time.

Instead I am giving a positive description, going to the heart of what I have confirmed in myself but also, in a move away from it, a moving back.

The three lines of entry into Dzogchen are simple: simplicity, pain, falling in love. Simplicity takes the form of seeing how tiring it is to go on describing something, wide open intelligence, as something that exists, and this includes even art and beautiful writing.

Pain is what I still feel, the fear of death being replaced by extinction, one-off extinction, in our every step. I don’t want death to become extinction. I miss death. I don’t want death itself to be lost.

Falling in love is the sovereignty of the female Guru as the fulfilment of a lifetime of misunderstanding of love. This is something everyone knows and can know. Love can never be fulfilled in the other, but only in the Great Mind of loving emptiness as purity.

Phowa: Transference

Transference is this other thing. In the time before Covid, there seemed no time in which to stretch to a possible transference. No time in which ‘no time’ might be contemplated as the time of now. Phowa is the opposite of attainture, that is to say, of endless slander.

It is like the example of not needing to imagine your mother to be your mother, as you have no fear due to thinking that she is not your mother.

Second Memory

I remembered recently that the first time I took MDMA all I could do was talk about Finnegans Wake, and specifically about the fact that it had been written at all.

It was Christmas. We were walking across a car park in the North and the winter wind seemed severe.

I remember that we hid in the supermarket and continued to talk.

Me and the girl who introduced me to ecstasy pills.

Rilke

Around the same time, the beginning of lockdown, a few of us were also following Ariana Reines’ free session called Rilking. We were reading through the angel poems, and I myself had the beginning of an identity in that direction. An inkling.

What was strangely amazing was that the transmission power of my Rinpoche’s transmissions subsumed the power of Rilke, which is incomparable, with ease. The ‘transference’ of a new identity for impermanence did a very simple manoeuvre.

It OutRilked Rilking, not that Rilke was touched or needed to be. Not that we needed to put to one side a thing.

Rilke via Reines, one great poet with another, was understood as amazing and free magic. But I in turn was stunned by how Rilke could not begin to keep up with my Rinpoche, indicating what is beyond poetry in another art. It was alchemy, on both channels. And it was broadcasting each day at the same fertile point.

‘Lockdown’—it becomes in time a magical word.

‘Early lockdown.’

The Second Time We Took Ecstasy

The second time we took ecstasy, everybody was dancing to great music downstairs and it was New Year’s Eve, the night after the first night, which had therefore been the night before New Year’s Eve.

Eventually we had to go upstairs because the pills were so strong. The effect felt insane and extended. We slumped against the wall and another girl from school joined us, Claire.

They both hugged me and for an hour at least, one on each side, they told me they were in love with me. I told them that it didn’t matter. I remember repeating this again and again, that it didn’t matter that they said they were in love with me.

I had an overwhelmingly clear sense of time passing by, of it having been gone.

It didn’t matter: these are such simple, well-known words. They now seem to mean so much.

So much more . . .

We Are Children

People stay children because they have to think a very hard thought. They know if they don’t, they won’t. When we are no longer children, we are already dead, literally.

In lockdown, at the beginning, it seemed I could be such a child, a child whose waiting could finally make sense. If we hold back from the world, it is because something is wrong.

We are allowed this. Waiting is a right.

It is because we are holding on to a dear and secret meaning that has to be confirmed.

Reading At The End

As I say, I realize that I have no idea anymore whether I have a right to hope I am wrong in my intimations. What if I am right? What, in that case, would I owe to you?

What would I tell my young daughter, were it announced that we only had a few years left?

On the one hand, what does a person need to know? Especially when we may still have millennia. On the other hand, what does it mean to not let someone know how it is?

Is the reader a daughter? How should she be protected? Is there a right not to know? What does it mean that some are better at knowing they need not know than others? Who is your Antigone and who is your Ismene?

Is this where we locate ‘privilege’?

Le Temps du Sida

One of the first things I read in lockdown was ‘Reader’s report on Michel Bounan’s Le Temps du Sida’. Somewhere along the line, Verso refused to publish Bounan’s work. The report contains this sentence:

The ecological crisis illustrates the fact that every illness that our civilization had claimed to have abolished is destined to return in a more aggravated form.

I held onto this fragile and immensely truthful sentence for what it is. I hope I still do.

I read back into the history of Bounan’s book, and found that Avital Ronell had read it in no small detail in an essay called ‘A Note on the Failure of Man’s Custodianship (AIDS Update)’.

In this essay Ronell refers to a certain unwillingness to read signs, ‘the failure to read AIDS’, and ‘the inability to read AIDS’. I was reminded from experience that this failure of reading would almost certainly happen again.

I think there has been a failure to read. I think there is an inability to read. More than that, there is a failure to read impermanence.

Perhaps reading has never taken place.

It Self-Reads

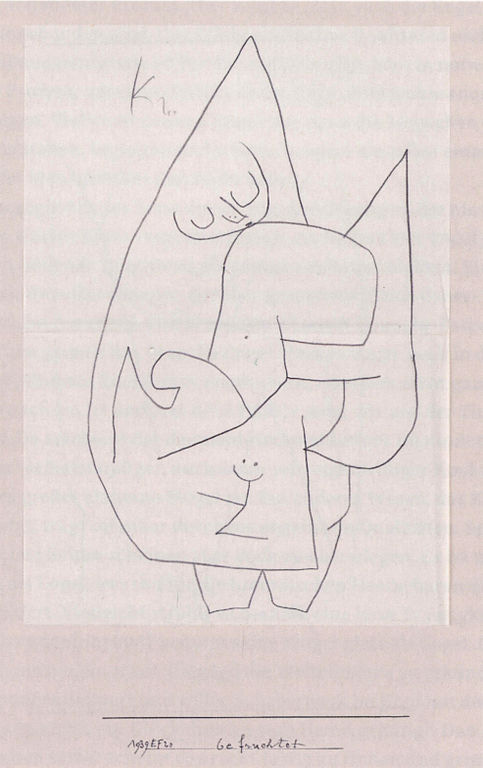

Years later, after those drug experiences, I would read Lacan on James Joyce. Lacan asks why the hell Joyce would write his final book. Where is the point? Lacan then uses a strange phrase worth thinking about. He says that Joyce’s final book ‘reads itself’.

🤍