THE FACE OF ELIZA DOUGLAS, PART 2: NOTES ON THE END OF THE UNIVERSE

After the end of the universe

The meaning of contemporary culture is cancellation. Cancellation employed by humans, cancellation that enslaves online life, cancellation before which we shrink away. This ‘cancellation’ is not just the cancellation that we know by the recent name ‘cancel culture’, though it passes through it, and makes itself known there. It is the larger force by which the human spirit is, at all times, swept away and made vulnerable, stretched to breaking point, killed, turned to stone.

To define cancellation negatively, and more broadly—it is that x which turns anybody subjected to it into a thing. Its main trope is the trope of petrification. In ‘Medusa’s Song’ by Eliza Douglas and Anne Imhof, from the music for the performance piece Faust, the stare of petrification is undecidably sang, brooded on, absorbed, and perhaps subsumed. What is ‘painted for the end of time’ here sings out clearly, as if the force of a more final cancellation could at least be known; and this no less a slaughter.

In Byung-Chul Han’s Psycho-Politics, Neo-Liberalism and New Technologies of Power, this cancellation is a form of explicit dictatorship and self-imprisonment. It is called, without further ado, the internet. In several forceful pages at the start of the book, Han reminds us that Capital is now the Capital of out-of-control auto-exploitation. Nobody needs to control us and overwork us in the present because in the Digital Panopticon, we control and overwork ourselves, and this puts Marxism out of a job. Society, according to Han’s logic, is unable to construct itself anew. It is stoned.

It is easy to underestimate the degree of violence that is here being done under the name of ‘cancellation’, let alone under the name ‘cancel culture’. To speak of ‘cancel culture’ is perhaps first of all to petrify a worse still form of violence (cancellation as such) into something apparently less threatening; extinction by a thousand first cuts.

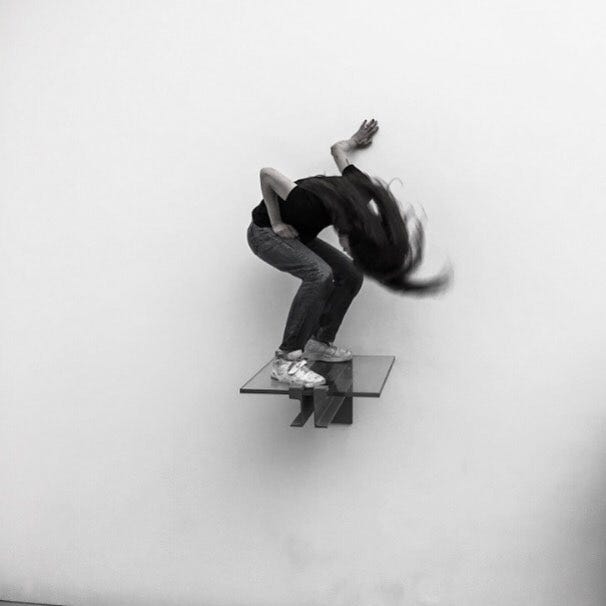

The face of Anne Imhof’s muse and fellow ‘image maker’, Eliza Douglas, is not necessarily a Medusaed face, but it is a face presented at the end of time. It is the face, the expression, of how ‘the ubiquitous element that is the end of the universe obtains exactly when nature is after nature’ (Iain Hamilton Grant). The faces of the Imhof troupe that made up the various performances of Faust in the summer of 2017 were faces at the very far end of something that may still be expanding for a time, amassing together, sculpted. This is a gang for the end of the universe, and how it adheres. You need look no further than Instagram, where images and movies of Faust were collected [see figures], for the allegory of the perfection of finalism’s image itself.

It is hard to express the pressures they must be under, what weight they have, what seriousness they might have yet become, or come into, like getting used to a new skin. Whether open to the viewer on Instagram grids or more directly ‘in the flesh’, or bemisted as is the case with the 2016 piece Angst II, the faces in an Imhof ‘image’ (as she prefers to call her work) are faces moving in atrophied and cancelled time. We might want to add ‘and yet still, they are moving’. Like the snow dancers in Matthew Barney’s 2019 Redoubt, they are still dancing without dancing. And yet that’s not quite it.

That they are images of this (the glaciation of movement and words) means they are not part of a movement that fetishes ‘cancellation’ as a ‘culture’, even as they undergo its final forms. They are not to be touched after all; their audience is ‘out of touch’, at a distance. They too, the ‘performers’, are at a distance. This orbital distance is crucial, a kind of token of time’s becoming-stone. Imhof’s are not images of online life but of an actual life after all; a life, to put it hyperbolically, after the afterlife, and yet now.

Forget Deletion

Is it possible to get away from the toxin of ‘cancel culture’ without forgetting one is petrified? In early 2019 Instagram images and videos of Anne Imhof’s Tate Modern piece Sex were available as more than a substitute for the performance itself. Crucially, the images gathered show that the figures (Douglas and Mickey Mahar, Billy Bultheel and Lea Welsch, Frances Chiaverini and others) are immersed in a contemporary culture that is suspended. The prime image of this is the AOC hoodie (and sometimes tee) which Douglas wears.

To talk about ‘cancel culture’ is itself a way of being dragged in and down, and Imhof’s ‘images’ keep a kind of distance open for another form of cancellation, something that can be painted for an available end of the universe. It could well be, in reality, that these are actually the figures for such an end, and they have that inscrutable urgency and dignity.

To say that Douglas and co. can go without belongings is crucial and also goes without saying. No performer carries their bedroom with them, for the most part, and yet here the fact that no image need be carried into the painting except one’s body, dasein-for-the-end-of-the-universe, is just what gives the performance a lack of fixation. To carry everything on you is to be in the more personal, and less dance-y, business of dispossession as culture.

Are these live beings (‘performers’) needing to be alive at all? For the long hours they are suspended in in-animation, do they eat and drink? To not need to live is not necessarily (the image seems to be saying) to lose the will to live or to cease to be.

Cancellation, as a culture, may just be a distraction from the extent of cancellation in which they may yet be and still have to choose to live.

No More Angels

Simone Weil writes in Gravity and Grace of how gravity ‘makes things come down, wings make them rise: what wings raised to the second power can make things come down without weight’.

It is not clear that the analysis of what may be called ‘end of time culture’, and no less its performance, allows anyone or anything to rise at all. Weil describes a rise and fall that is far from directly metrical. No doubt to be dispossessed, and to stare down what is more than an end, is to encounter weight and weightlessness at the same time, and yet not every comedown knows how to raise to the second power.

The danger in ‘dispossession culture’ is not in the one moment it turns its gaze towards you (Imhof shows that is of relatively little interest), but in the absence of an image of absolute petrification. To not even have time and space in which to breathe the end of the universe as a Thing that is real for flesh makes ‘cancel culture’ look like a party.

That the nexus moment in contemporary culture is where these two Gorgons meet

extinction/cancellation

and where spills out the question of ‘will we remember the morning light’, ‘will we remember the evening’, is the way this song is made, and the way its incredible (almost architectural) sobriety functions. To be a ‘leader’ here is not to go down even though it is subservience and servitude (‘at your service’). To be cancelled absolutely (‘feast upon me, that’s true love’) is to have nothing to do with ‘culture’ ever again. It is to see that where the end of time adheres, there is one, perhaps, more time.