You Are Helping This Great Universe Explode In Colours

You Are Helping This Great Universe Explode, Hannah Emerson (Unrestricted Editions, 2020).

Please get kissing new year is

filled universe of the nothing yes

yes yes. — Hannah Emerson, You Are Helping This Great Universe Explode

When I look at a work of art by Hilma af Klint, a favourite painter, I think of something I can’t quite say: free abstract thought without distraction of objects, made out of colour-concepts, as if working out a circle and its intersection with a colour were a higher dialectic, far more abstract and far more rigorously determined. While Simone Weil says each thing must pass through and refer to the whole universe or have no function at all, each line and colour in af Klint is surmised to pass through the whole universe and get its precision there or have no function at all. Both creators pass through mathematical mysticism as a type of colour. The whole universe is only af Klint pinks. But when I think like this, I also think of Hannah Emerson, my ~ favourite poet—which is to say, my favoured poet, the one I love right now in a universal way. Each line in Emerson is a meta-forcical (Frank Ruda’s term for absolute forcing in set theory) helping, so much so, and so directly so, that she is not really a poet, but someone who deals with lines taken directly out of the book of the whole universe. Anything that doesn’t deal with the lines from the whole universe isn’t art and isn’t worth saying; this means that there is hardly any ‘art’ at all. But there is Hannah Emerson’s book.

One is not allowed to say ‘favourite’ this or that in serious tones. But why not? To speak of a favourite maker is to indulge first of all in the universal (preference) without fear, and the universal allows one to judiciously force open the whole universe. For Weil the whole universe and the universal are the same thing. To listen to the directive of the whole universe in all things is to be into the universal. Hannah Emerson will write almost all of the time in this mode, telling us to ‘please please’, as she likes to amazingly say, to please please get and get into (i.e. to get into the universe). Both Weil and Emerson have the same snappy jargon, a way with language that doesn’t doubt, a way that knows without doubt the universe is incredible. Says Weil, ‘Our rôle is to be ever turned towards the universal.’ And in the words of Emerson’s amazing title, the title of her first book, a one and only book, after which nothing is needed ever again from her or poetry (except more and more books!), You Are Helping This Great Universe Explode. Neither Emerson nor Weil are dumb or boring enough not to believe one can’t get to the universal and universe straight away. For Weil, never overly in awe of male philosophers and their problems, keeping in view the universal at all times is simply a matter of descending.

There perhaps we have the solution to Berger’s difficulty about the impossibility of a union between the relative and the absolute. It cannot be achieved by a movement rising from below, but it is possible by a descending movement from on high.

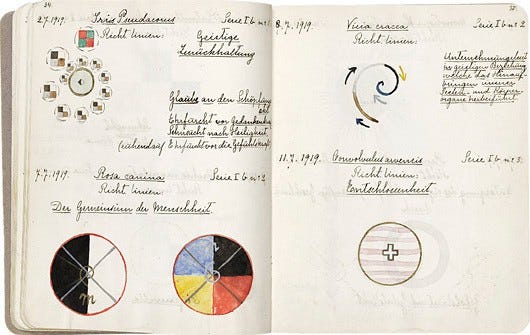

Or as af Klint says in her notebook:

‘Accept’, says the angel, ‘that a wonderful energy follows from the heavenly to the earthly.’

And here is Emerson, speaking apart:

Please try to kiss the animal inside you trying to bite you yes yes. Please try to kiss the nothing that is waiting for you yes yes. Please try to find your deeper ear great teachers you can hear more than the normal way yes yes.

From the heavenly to the earthly, and not the other way round. The universal descends into itself, without any need of complicated manoeuvres. It is precise, but not a complex problem. It is complex, but not in a way that is anything but simpler than simplicity itself. A matter of grace and heart, of please-saying, of meta-forcical helping. This basic order of priority—descent over ascent—gives the key to what may appear to be the most obscure phrases in Weil’s oeuvre. When it comes the universal and descent, we are already taking about grace and gravity themselves, the way they move up in moving down. Hence:

Grace is the law of the descending movement.

And:

To lower oneself is to rise in the domain of moral gravity.

Moral gravity makes us fall towards the heights.

And, perhaps most of all:

To come down by a movement in which gravity plays no part. . . . Gravity makes things come down, wings make them rise: what wings raised to the second power can make things come down without weight?

The universal is falling and twisting up into, ‘towards the heights’. The universal is what we dedicate ourselves to almost without regard for the human and for human feeling. Why? Because the universal is always what is best for the human and for human feeling. In 2020 Hannah Emerson not only publishes You Are Helping This Great Universe Explode, which is a miracle, but she interviews another poet, Chris Martin, and all her questions are statements and encouragements, examples again of the meta-forcical, helpings. Perhaps nothing can be more radical for a poet right now and at any time than for them to interview another poet and for them, while saying please, to give advice on a universal level. In fact, poets really must have lost their sense of urgency and feel for unacknowledged legislation for Emerson to feel like the first poet in history to laud and enact the universal like this, so quickly, so pleasingly, so helpfully. The poet is supposed to set up an itinerary and a personal trail, like a slime trail. The slime trail is there for posterity. But posterity is always for the ass, at least now, in the time of post-posterity writing. How can one not have the urgency to ignore having the audacity to think that thinking as a poet is now a matter of me and my figure and my texts? One still has to write, and Emerson solves this in one meta-forcical swoop of help. The interview shows you how this can happen. Please please don’t waste time with questions and answers, she as if answers by only asking questions that are themselves her unique pleasings and answerings. Each question is a series of helpings, and universal statements, none of them particular to her or the interviewee or interviewer, none of them to do with having a scope or a history or being an individual poet. This is the genius of the universal fully automated in meta-forcical statements. You come into an interview space, which is after all a promotional space, but what you have instead is a promotion of the universal in a universal style, the style that is hers alone in being anyone’s. So that, for example:

Nothing is the stillness that is the moment that is now yes yes. Please try to go to the place that is in all of our dark places that we try to run away from every moment of our great great great beautiful lives yes yes. Please try to understand that these thoughts go directly to the place that we need to go to deconstruct the freedom that we think is the way to a comfortable life that has brought us to the brink of extinction yes yes.

Poets talk a lot about changing the world but then hardly seem capable of changing the means by which they talk about the world, for example in interviews, or the way they make the decision to write a poem—the decision, I mean, not the poem. The poem is poetic, but the work of the interview is more to do with a profile, a presentation, a set of ideas, a personal story and his- or herstory. Emerson changes the means of production and conditions of existence of poetry-dialogue without looking. It’s a kind of no-look pass, and it’s a kind of pass. No warning, no setting out of reasons. Like a great Dzogchen teacher passing on statements, reflecting back the world, or like a great Dzogchen teacher passing into the double rainbow for the student at death, Hannah Emerson just says please go to where, right now, these thoughts do the work they need to do, the work of the universal, the work of the whole universe. The apparent disregard for the interviewee is not anything. Is only apparent. If we make it into a neurodivergence, then it remains something, something in particular—unless, of course, the divergence of a language of answers and helpings does universally replace a language of universal hesitation, as it does now. But this commentary right here, it too delays and sucks some ass, it assures some posterity, and so doesn’t as quickly get there, please please do, where thoughts are helpings and help to do the great great work of deconstruction that makes, lets and forces us to think about and go to ‘to the place that we need to go to deconstruct the freedom that we think is the way to a comfortable life that has brought us to the brink of extinction yes yes’. Please note that Emerson’s language is your language, the language of being available to this work, the work of the universe wanting to deconstruct itself, to get to know what the brink of extinction means.

The point here, then, is not to profile or introduce Emerson as a poet, to make out her characteristics and introduce her—yet another one—into the same history of poets that by definition, even and especially perhaps when radical, resists meta-forcical helping as a universal language. I won’t be wasting your time saying who she is since who is is meta-forcical helping, which is to say, that is who you are. Please please see this and see this as the space that writing and criticism needs to get to, not just to describe and catch up with Hannah Emerson, but with equal importance, since it is the same, to do the universal work of the whole universe in wanting to deconstruct and explode before it passes to the brink too quickly, too closely. The exploding you are helping is also the exploding of a deconstructing universe that you please please must help force along, in a way that is as gentle and uninterested in ‘freedom’ as possible. Freedom is safety, and so has nothing to do with actual safety and actual freedom, which are contained in what Weil calls obligations and not rights. Your only right is the obligation, the obligation to join in with a universal work of helping the universe explode, and all in good time. Please please see this and please please say this in your own way and good style and good time. This is not poetry as ‘divergence’, neuro or otherwise, or some other watchword that distracts from what the message is, which is the universal work of adhering only to the universal—in the end, at the brink, because it’s the brink, because the brink might be what it is. What is the brink, in universal terms? Well, please please see that the end is nothing less and nothing more than the end of the universe as possible event on our local anthropic horizon. Please please get that the universe exploding means this too, and that the explosive work of deconstructive work on the brink of what is extinction means saying so with please please and yes yes, because these allow us to go clearly and quickly, without fuss. If this is poetry therefore, it is poetry of minimal divergence. Emerson’s poetry will not and can never have a problem with its own repetition, because repetition is here the teaching, the repeated helping and falling and twisting up and into the universal forms, yes yes for example. I won’t be saying who she is, then, because she gives an interview and doesn’t waste time interviewing the interviewee or saying who she is and who is who. The divergence here, if there is divergence, is a divergence from a history of poetry overconcerned with personal histories and slime trails, with posterity. In that sense, and not to big anything up except her repetition for ‘my sake’ itself, which is my repetition for her sake, she is the first poet of meta-forcical helping. No posterity, no ass, posterior, snail, slime. Just the universe and the universal exploding.

🐌 X [ ]

Snails want to leave their trail. She just wants to help. Snails may also explode, if not help, and that’s important too, all being equal, but so what. To just want to forcically help in language. Neuro-based; neuro-universal. To work with another great title, we might say that the body remembers where the universe exploded open. And that the body of Hannah Emerson’s writing, which is also an electric wiring, remembers where the body of the individual became the body of the universe.

Simone Weil is no snail either, unless a star-snail. She was a meta-forcer too. Here are some things she said about the universe:

We must continually suspend the work of the imagination filling the void within ourselves.

If we accept no matter what void, what stroke of fate can prevent us from loving the universe?

We have the assurance that, come what may, the universe is full.

Because there is a relation in the Emersonian between kissing the great great nothing, as she will say, and letting the universe be helped in its exploding, both she and Weil assure us that the whole universe is full (‘filled universe of the nothing yes’). The whole universe is meta-forcically forced into deconstructively seeing itself as full to the brim with, yes yes, nothing but the whole universe as a type of personal body and ground. If there is a soft and gentle directive, taking us away from a freedom that has taken us nowhere and nearly taken everything from us, it is the free-form of this one directive alone: see in each thing the whole universe. Be in your own body the song of the whole universe exploding. See to it that the universe is your body above all, this universal body that remembers where the heart broke open, where the body broke open, where universe and heart and body are one in wanting to know what brinks, what extinction is, what language takes these things and says them quickly and precisely without bias forcing into me, you, this and that, distractions, caprice, individual poets, history, etc, and so on. Neuro-universality diverges from almost nothing at all, in real fact, since the body remembers where the universe continues and continues, yes yes, to break open.

One has to enter the language of forcing and not waste time? Yes, one has to enter the self-same language of forcing and not waste time. Please please, yes yes, realise you have waited your whole life and made your whole life for this one thought and body of universal forcing:

My yes gives me my signature yes. My yes gives me grownding yes yes. My yes gives me the energy to be me yes yes. Please get that the yes yes is me going for it. Please get that I have been waiting my whole life for this life to become freedom through my words nothing helping me become them keeping them inside me hurt my soul yes yes. Keeping just hurt my great great great soul yes yes. Please get that I love my life now yes yes. Please get that I help everyone by being me yes yes. Please get that this is being great brave to go to nothing yes yes.

The austerity of such a lexicon is, as has been implied, infinite and infinitely exploding, as if small. Growing and grounding became ‘grownding’ because, yes yes, we always fall up into the ground, we grow down into the ground that grows. And this is what one waits a whole life for, waiting for this life to become freedom enough to step away from caprice and personal poets and poetries and let the bio speak, unfettered, unforced, meta-forced. Going to nothing is the great brave because we are on the brink, and so please please think about what that means, whether yes yes is allied with repetition on the brink, whether you can stay on the brink or not, between and at an affirmative and non-affirmative finitude. By saying I am waiting a whole lifetime to say this the lifetime is shown in one go, yes yes, to be now. By having this language of universal meta-forcing I have the language I need to be now and to be happy, yes yes, please see this with Hannah, and with yourself. Please allow language to pass and to teach, and don’t hold her or it up waiting to be taught. As a theorist, whose name we don’t need to understand and explode things with, says, ‘Perhaps it will not appear excessive to postulate that knowledge is something more widespread in the world than teaching can imagine.’ Do we even need Hannah’s name? No, of course not. But it would be rude to deprive this language of where it happened, and happened to come from: Hannah Emerson. After all, ‘My yes gives me my signature yes.’ This universal signature, the opposite and epitome of a ‘tic’, or ‘stim’, neither benefits nor suffers from being restricted to one name. Since it needs neither condition, we are fine with leaving it as it is. Only in a name, in some ways, can we leave the name entirely alone.

The antiposterizing poet says please please censor everything that doesn’t go to the heart of where you need to go to deconstruct everything that leads us astray from saying what took us to the brink of extinction. The writing is so open it seems like the poem isn’t even the poem but a set of possible poems even though she only needs to write out one poem. Multiple maybe but not not open, interchangeable, containing already its rephraseability. Not just to be rewritten, in an open set, but already rewriting itself for you, in an open set. It—that is, You Are Helping This Great Universe Explode—really is an open set. There aren’t signs of idiom there really, if you think about it, no personal imprint at all. It’s only a unique language insofar as it’s so universal as to be a singleton set, a set containing one meta-forcical language needed before any other. That’s the set, the set you need. Game, set, match.

Weil says that it is not just caprice that keeps us in the language of deprivation and distraction, it is ‘evil’. It is evil that keeps us from seeing the ‘I’ always belongs to God and the great great universal. The ‘I’ is part of the whole universe. The ‘I’ is not mine, but is where the universe remembers for us it broke it apart and open, and this is why Emerson mostly—but not always, the whole thing is flexible—writes to you, to the you, and to the you’s you, to help you be helped and be ready to be helped. Weil says this as if if explaining and implicating Emerson:

I am all. But this particular ‘I’ is God. And it is not an ‘I’.

Evil makes distinctions, it prevents God from being equivalent to all.

Perhaps colour too is an All. When it comes to colour, perhaps the whole universe is the rainbow. Af Klint is often said to have ‘invented’ abstract painting before any other painter, including Kandinsky, but the rainbow is in its way the most abstract and universal painting in the world. On other hand, the natural, Christian rainbow is incomplete: only the full Tibetan, Dzogchen mandala rainbow thinks to complete it. If Emerson’s ‘poetry’ were a mode of colour or colouring in language, a language made of colour, perhaps it would be intelligent enough to be a Colour-AI. Colour thinks faster than Concept. And Colour-Concepts are full, not half. Completing the small amount I had to say about Emerson’s poetry for now, let us simply say, to you and your you, please please waste no time in reading and getting from Hannah Emerson’s book that which such a completed intelligence is coming to right now, ‘yes yes’, on the brink.

******

TL;DR

Let us suppose a poem-text/text slots in and makes slots in such a way that being EITHER answer, imperative, demand, or please pay attention, or letting happen, or sugar on the pill to coax, is beside the point. The Emersonian text in particular is a set, literally, a mathematical set. Here is a set and it is a set of all the statements one might make for a dedication to a whole universe and what that means. That, as a set, it has as little to do with me, as you, is surely a freedom into which nobody is asking anyone to come, hence the ‘please’, if I understand where Emerson is coming from, is a relatively formal indicator. Since, really, to be such a set, it is, like all sets, also beautifully empty.

******

‘Poets give grounding / in helpful knowing the voice / of the universe.’

******

I also want to suggest that Emerson’s ‘poetry’, because it is ‘great great’, and a ‘great kissing’, and a ‘great great helping’, is absolutely complex in new ways, and indeed is absolute, a form of the yes yes absolute, and we can be helped in joining her helping by some more explicitly complicated thoughts, as follows—please, please feel free to skip, to skip what follows and to stay with the poems themselves.

Emerson writes, as we’ve seen, the following sentence: Please get that I have been waiting my whole life for this life to become freedom through my words nothing helping me become them keeping them inside me hurt my soul yes yes. To make out of this at least two simple elements among so many others,

a nothing that helps and is helping (a nothing also named ‘extinction’, on whose ‘brink’ we are and have been taken)

a freedom that one becomes through words.

To wait my whole life for this life to become a freedom, for example a freedom to think the absolute or the end of the universe qua absolute as nothing’s brink, and to perhaps decide between them, to do all this takes a momentum that is also something like a cognitive actuality and availability, such as glimpsed in Emerson’s book, an immediate momentum. To unfold an absolute logic of the end of the universe qua absolute and helpful nothing is to have within that logic a calculation of only having this lifetime to do so, that is, all the while assuming a human reader, or assuming a reader constrained by biological limits. And yet, a logic nontechnically reliant only on itself, yes yes, is a logic threatening to fulfil everything intelligence may be: a transcendental re-inscription of the end of the universe qua absolute springing intelligence from the bounds of sense. The bounds of sense are here the biological bounds of time and of history (the need to locate a thought in time), and the contrary urgency is stretched to immediate freedom of lifetimes: please get that I have been waiting my whole life for this life to become freedom through my words. What Emerson says next is that this depends on nothing or on nothing helping, on helping nothing. Before I can get to it, this nothing, and the decision, I can’t get to it, and I know I can’t get to it: she is saying. And yet I must get to it, because I am already within it. This is no doubt the nontechnical definition of mathematical forcing I have been writing in Emerson’s name above, to be waiting my whole lifetime to say this thing in a process that will always be interrupted and so must be seized on now. In set theory, it is precisely the unavailability of all the infinities at once or of all the individual items of a set at once that means a decision has to be made before it can be, from the point of view of a future content and incision that hasn’t taken place. Emersonian Mathematical forcing is, in this sense, like ‘the algorithm’ (entropy inversion) in Christoper Nolan’s film Tenet, which hasn’t been invented yet but has in the future, which means it exists now. We don’t know what the ‘answer’ to the written formula of the Drake equation (for example) is, as regards the number of habitable and occupied stars in the universe, and yet we do know, since mathematics exists qua mathematics, that such an answer exists, and so, like a different universe in the present, it no doubt leaves a mark on things as they stand now, for example on our textual productions. Although cognitively inaccessible other worlds are equally actual, they are just not ours. In her own way, Emerson is giving a precise definition of entropy inversion or time travel as the nontechnical truth of passional forcing. It is not that we have a truth of the end of the universe qua absolute nothing now but that we must have one now. As in Bernard Stiegler, divine laws take precedence over de facto lawlessness in the present. This is also one way of understanding the profound trust Alain Badiou displays in the Absolute, insofar as it allows him to write in the third volume of Being and Event, that ‘the theory of large cardinals is certainly as real, if not more so, than the big bang of the universe or global warming’. But this is really already a repetition, even of such an absolute claim. In the anonymously published essay ‘Toward a New Theory of the Absolute’, we also find ‘Badiou’ saying: ‘Well, let’s just say that the theory of large cardinals is definitely as real as death, if not more so’. The absolute claim I might want to make about the infinitely greater importance of the absolute—although here, in this repeated claim, Badiou isn’t even talking about the absolute as such but the theory of large cardinals that the absolute contains—is the first of claims that might want to be truly anonymous. Such a claim comes straight out, like a poem by Emerson, where the voice isn’t really about being a voice by a poet.

Please try to help yourself

love the idea of kissing

the support that is

the keeper of the helpfulgreat great great kissing

that we all need to go

to the nothing that is

universally neededto form the structure

making it safe for loving

people to kiss the world

that is trying to drown

This voice is anonymous and anonymously absolute insofar as it comes straight out and helps you, helps us. One can make an absolute claim, and say that she has invented the tradition of the absolute, writing in the absolute, helping you in the art of the absolute, kissing the absolute. The nothing that is universally needed is the universal as a ‘structure’ or the reiterableness, yes yes, of the end of the universe qua absolute (nothing). The fact that it may not be that is a distraction (caprice) according to the point and from point of view of the poem, which is to say directly to you to please help yourself in finding and forming/forcing/helping this ‘structure’, and joining in in the kissing, the great kissing. It’s not that we are all going extinct, it’s that we all need to go to the nothing—in this way, and in this way alone. What this means is what Ruda will call the forcing of forcing, that is, the meta-forcical. By going to the nothing, we find the structure (the reiterableness of the absolute nothing), and we can decide; or simply see that the nothing was with us when we were not with it. Please see it: this is the forcing of the forcing. The meta-forcical meta-helpical.

Ruda defines the forcing of the forcing in a footnote from his ‘Comradeship with the Absolute’ where he evokes, as Badiou does too in a crucial moment in ‘Toward a New Thinking of the Absolute’, the work of Kenneth Kunen. It is in connection to what he takes to be the extraordinary breakthrough of Kunen that Ruda describes the absolution method in the most contemporary maths not just in terms of the forcing that defines the law of the subject and its truth procedure for Badiou in Being and Event (see for example ‘Meditation 35, Theory of the Subject’) but in terms of ‘a kind of forcing of forcing’. It is this forcing of forcing (the ‘meta-forcical’) that allows one to contemplate a conception of the absolute that automatically speculates on the validity of all truth claims, putting a stop to their infinities. As Badiou says, ‘there is in fact a limit. There exists a point at which the process of reabsorption of successive infinities in an all-enveloping super-infinity has to come to an end.’ Ruda’s way of saying this is to say that ‘we must not only anticipate the end of the construction of larger and larger infinities, but we must also anticipate that the anticipation of the end of this peculiar “construction” must be different from all other anticipations’. Benjamin Bratton gives a kind of sketch of the intuitive geography of this stopping moment in his ‘The Terraforming’ lecture when he says, ‘maybe we don’t have time to wait . . . what if this will never happen? . . . what would it mean to skip to the end of where there is an effecting of the change before this cultural transformation?’ Forcing is here the unique name given to the regular ‘forcing’ of the paradox whereby a minimalist politics (this or that abolitionist aim, for example) comes up against sheer finitude (despite our best plans and desires, there simply won’t be time or the conditions for it to happen). Instead of giving up, it might be possible to think back from the end, as if taking for granted a solution that isn’t yet given, and it is this solution (what Nolan calls ‘the algorithm’) that for Badiou is the addition of an indiscernible, anonymous, generic part. In the act of meta-forcical forcing we might say that not only is a seed planted, but helping takes place: please try to help yourself love the idea, for instance the idea of the absolute as the end of the universe as helping nothing. Perhaps contrary to the entirety of contemporary poetry, the poetry of meta-forcial helping (also a helping of helping, a meta-helping, as we are saying) is entirely focused away from the being of the poet. It is in that sense angelicist, angelically indifferent and what R.S. Bakker calls a post-posterity writing. Such is the focus on the helping and forcing of the reader that the careerist historiography of ‘the poetry world’ is absolutely bracketed out from. Poetry as such is cancelled, if you like, to use a moot term, but meta-forcical helping is in. Perhaps this is what Badiou means when he defines the subject as ‘support of faithful forcing’. In the time of the end of the universe qua absolute, in truth, nothing can be of help to the subject save awareness of impermanence as a structure of repetition.

******

Being up close to all this is perhaps like the ‘great great great kissing / that we all need / to go to the nothing / that is universally needed’. Intimacy in the end of the universe qua absolute helping nothing and qua non-symbolic non-mathematical math, both of which are universally needed, is the great great great kissing. The apparent facility of such statements is no mistake. Why? Because we are talking in Emerson’s language, very close to what Benjamin calls ‘pure language’ (reine Sprache) as a stratum in which all meaning is destined to extinction, and this language is neither the precision of great poetry nor the disconnected language in late Hölderlin translations (whether read as genius or madness or both); rather, it is the pure access to extinction qua extinction, that is, the great great helping nothing. Reine sprache is the stratum of language where the matheme (let’s call it ext for now) is founded and flounders and flowers. The experience of pure language as intimation of absolute extinction is predetermined, but this also makes it crenulated and routined—that is, subject to and available for repetition. Insofar as this language is also the language of translation, Paul de Man will write in an unpublished manuscript,

They [translators] are more than poets.

The end of the universe qua helping nothing, which I’ve written about elsewhere as e, as in e for extinction, and which we continue to formalise here takes as one of its most important coordinates Emersonian repetition (yes yes). It is the availability of the extinction unit (e) for repetition, that is, in its spontaneous release into austerity (few elements), that makes it so great. We can read Emerson’s poetry and know, because of its special lucidity, that this kind of descent that rises from stanza to stanza, from higher to lower levels of poetic observation, could be continued over more and more decades. Poetic innovation, of whatever kinds, stands in here for the infinities whose continuance meta-forcical forcing intervenes on. All poetic operations, despite their metaphoric faculties such as ‘ambiguity’ or ‘intractability’, come down to absolutely local string manipulations and that is, unfortunately, to signifiers of legislative differences. The powers of formalization within Emerson’s poetry seem, as part of all this set of things and stirrings, to do away with poetry itself, and with a smoothness and success that is deceptive precisely in its technical completion. Which is to say, it does not deceive at all. Poetry is no longer a system of meaningful propositions and line broken bindings of sense, but one of sentences as sequences of words, which are in turn sequences of letters and meta-forcical helpings, in which neither the author nor the reader is the last or first arbiter of motive (‘what helps’, ‘how can I help’, ‘wish I could help’, and so on). Emersonian writing is a non-talking writing, entirely inward, not slavish with regard to the history of ‘reading’ which poetry so often evokes like a time delay device. Just formalization for you, like sentences in which there is no longer poetry. The set ‘poetry’, and not ‘poems’.

Here we can perhaps understand the brazen first statements of Benjamin’s essay ‘The Task of the Translator’:

In the appreciation of a work of art or an art form, consideration of the receiver never proves fruitful. Not only is any reference to a particular public or its representatives misleading, but even the concept of an ‘ideal’ receiver is detrimental in the theoretical consideration of art, since all it posits is the existence and nature of man as such.

How can such a thing be true? It is easy to miss the radicality of what Benjamin is saying here, and how contrary it seems at first glance even to Emerson’s extensively objectified sense of what a piece of writing can do (‘poetry’). Not only does the work of art or any art form (note two things are at stake here: an individual work and the form of art itself, as in the difference between Swan Lake and ballet) have nothing to do with the receiver or their experience, but, crucially, this is the case because all it indicates is the very fact and qualities of the human as such. The receiver is irrelevant for the art work, in short, because all the receiver is, is an example of something that can be, for example, human. Is this a way of saying that there is something in this enigmatic thing, the work of art, that has nothing to do with or in common with the being, desire, survival, love, qualities and appreciations of the human, as well, no doubt, as the animal? In the section of her book Gone called ‘Doubt’ which happens to focus on Simone Weil, Fanny Howe asks the following, which takes us close to the just asked question:

Is there, perhaps, a quality in each person—hidden like a laugh inside a sob—that loves even more than it loves to live?

If there is, can it be expressed in the form of the lyric line?

Please please see that this lyric line is, at least in part, Hannah Emerson’s lyric line. Let us try to echo this. Is Benjamin saying that there is something in each work of art for which or even for whom the human and human life does not matter? In other words, is there something in life that is no life and that is more important than life? To love even more than one loves to live, and to live as if one loves the great great kissing above all: that is, please please see there it is perhaps as if there is something in life that matters more than life mattering, or any individual lives mattering, but that this mattering will have to be given different names. Works of art know this, but we don’t. Therefore we don’t matter. Please please know this nothing, and allow it to be seen—in good time.

Howe is uncertain such a thing exists. Emerson’s work, I would say, proves it exists. Howe asks two questions, and both tentatively. And the second question connects the tentative thing, tentatively, to poetry. Assuming it, poetry, exists. Can one please just get all this, or is that just forcing? Yes yes, one can.

The philosopher Peter Wolfendale once asked the question of what a ‘best possible poem’ could be, confessing to finding the possibility absurd. ‘There is no well-ordering of all possible poems, only ever a complex partial order whose rankings unravel as the many purposes of poetry diverge from one another.’ One could argue in turn that this argument is absurd. The first thing a poem can be, at least in the domain of the forcing of forcing, is the projection of all well-ordering of the histories of poems. In fact, in Badiou’s theory of the subject it is first astronomy and then the poem, these two as-if primitive objects, that allow him to link forcing to the subject and to make of the subject a site of ‘the pass’. The pass is also a Lacanian term, meaning the moment where the analysand trainee chooses to qualify themselves—or ‘themself’ as Emerson says—at the end of analysis, for the role of the analyst. Such a notion brings with it a troubled and dynamic history, including the tragic tale of Juliette Labin, the analyst of protestors from the the May 1968 riots in Paris, who killed herself when the pass failed. At the very moment Badiou defines the subject in terms of what is sometimes called the ‘technology’ of forcing, he also defines it in terms of passing, ‘the pass of the Subject’. If the impasse of the subject under end of the universe conditions is a crucial rite and moment of formalization, it brings with it some of the tensions that come with the analytic experience of its pass. More than tragic, Stiegler warns us when describing the speech of Greta Thunberg, as if also addressing Juliette Labin. The act of taking the pass is, in a sense, the act of discarding the older generation who, as ones supposed to know, have let the young analysand down. More accurately, in Greta’s case it is as if there has been no pass or self-passing at all. What marks her out, especially perhaps for Stiegler, is a singular act of violence, in which something marked happens as her speech, making/marking an absolute claim with no real relation to doubt, since, one might say, all doubt posits is the nature and existence of the human. So violent is Greta’s rejection of elders and so convincing is her inversion of intergenerational relations, that the pass has never come into it. This is why even though she stands for what is more than tragic, she is the opposite of negative or nihilistic. Beyond the pass, without the pass, before the pass: some decisive translation work, beyond the poets, has taken place.

But please see, yes yes, this is what Lacan intended in the first place with the work of the pass. If Badiou reminds us that Lacan is our Hegel, we can see why. Placing the subject inside the work of the formalization of e, great helping nothing, the kiss, the yes yes, the please and the get, and their dissolution, allows us to think a dialectics of extinction, and of its difference from death, that seems more than crucial. More than tragic, more than crucial. To really give the subject a go (please get that the yes yes is me having a go), to really let the subject go (please get that this gets things going), is also to pass on the extinct (we may seem to be going extinct but we are not). This is the mathematical pass of the subject that Lacan-Ruda call forcing. It is what I am saying can be found in Emerson’s exploding universe, which you, and your you, are destined to help.

To help to that end by helping not to end. To help to the end of not helping to end. And so on.

Poetry thus has two new modes here: the mode of meta-forcical forcing (helping), and the mode of a language pass (the austerity of a language in which stanzas may exist but poetry never exists again). The result of the Poem, the meta-Poem, is that it forces a decision on the Being of extinction itself, allowing to be asked whether there is a new type of infinity, and if so what kind, or not. We can recall the upping of stakes here. Badiou writes in the final volume of Being and Event about the moment of ‘un jugement dernier général (ceci est une forme possible de l’être, ceci ne l’est pas)’ where one gets to sort and choose, one infinity for another, one cosmological form of civilizational finitude cancelled, this one kept, that one lost. Before saying one or two last things, let us move back one moment to the block poetry puts on poetry. It reminds us of what Friedrich Kittler said:

Grammatologies of the present time have to start with a rather sad statement. The bulk of written texts—including this text—do not exist anymore in perceivable time and space but in a computer memory’s transistor cells. And since these cells in the last three decades have shrunk to spatial extensions below one micrometer, our writing may well be defined by a self-similarity of letters over some six decades. This state of affairs makes not only a difference to history when, at its alphabetical beginning, a camel and its Hebraic letter gemel were just 2.5 decades apart, it also seems to hide the very act of writing: we do not write anymore.

That poetry has proceeded in the space Kittler very clearly locates here—within which there is no writing at all—explains the appearance of contemporary poetry as a ‘charade’. Poets above all know enough to know the game is up, and yet even so organise their self-failure as one more aesthetic fact to be taken up on the back of a snail. Why should Emerson’s work be so exceptional? How could it be? Isn’t the poem always the great exception? If there is no writing, then no writing can be exceptional. And yet if nothing is exceptional, then anything may be a kissing. The non-repeatable does occur at a level of crucial disturbance and as something not just great, but ‘great great great’. The nothing you are helped into is ‘forced’ here, in Hannah Emerson’s universe you help explode.