'LEGALIZE HEROIN': NOTES ON NYC LITERATURE, OLD AND NEW

impressions on early internet writing and the new New York novel. s/o s/o so/o, just notes

The internet, like the unconscious, has no sense of time. While it appears to exist only in the present, we are actually free to move forwards and backwards on it at will. Thinking about the history of internet writing, I remember for example Zachary German. I remember Zachary German far more strongly than I (presently) remember Tao Lin because Zachary German didn’t give a fuck. Zachary German didn’t give a fuck a lot and refused, after a certain point, to have a career and so everything he said left a deeper impression on me.1

I remember a Facebook post Zachary German made on the day Donald Trump was elected. German’s post that day was ‘LEGALIZE HEROIN’ and when he posted that on the day Donald Trump was elected I didn’t know it was the name of a song but it seemed like he was using it anyway to say that the day Donald Trump was elected was a day on which you might want to ‘legalize heroin’.

In 2015 Zachary German released an e-book called Thank You with AVF Press. Not too many people seemed to read or know that Thank You existed.

My impression at the time was something like: Zachary German released Thank You after the end, after he was known to have stopped writing, and before, I think, he started to go under the name Jocktober the Mesh.2

I like things that exist after people stop. They leave a deep impression. They have far more aura than the things left by people who are always carrying on. Most people carry on and are incapable of giving the impression they could have stopped and it’s almost like you get to the point where the only impression you can imagine being left is the impression left by someone who showed you it was possible to stop.

Like Brecht said, we find it very hard to say the most simple words, the ones that would break everyone’s heart. What Brecht wrote reminds me of the impression left by Z.G.:

And I always thought: the very simplest words Must be enough. When I say what things are like Everyone’s hearts must be torn to shreds.

In a clip from the documentary Shitty Youth (2012), in which German had started to stop, he says what things are like,

I don’t know, I just like, seems like everything we do is bad and like non-sustainable. Like everything we do besides killing ourselves.

How things are. What they are like. Legalize heroin. Break everyone’s hearts.

.

Imagine I came out and said something dumb like, ‘I remember Zachary German because he didn’t give a fuck.’ That already sounds imaginary, like a way of not disclosing something else. But part of what I think I pretend to be able to mean is that I saw him not give a fuck and that others said of him that he didn’t give a fuck and that this is a way of talking about myself—or at least about something else. Apparently Zachary German ‘excluded everyone. Everyone on the internet. All his fans. People who were paying attention to him, he was cruel to.’ Is it necessary to repeat just that act of exclusion to say how things are? It seems to me that everyone will tell you there are other options but that before you know it life gets in the way and that what most people do is a way of getting in the way.

When referring to Zachary German telling a critic to ‘suck a robo cock’, Erik Stinson once said,

So it wasn’t cool, it just had uh . . . that’s the Sublime.

It’s true that that’s the Sublime. It’s the sublime in Kant and the sublime in Kant has a strange place in relation to the beautiful (it kind of comes after the beautiful and after aesthetics itself). In fact, the Sublime itself is pretty much the jump in Kant from the mathematical to the dynamical sublime and the way this jump is a gap, and can’t really be explained. All of that, once you know all about it, is why saying ‘suck a robo dick’ at a certain moment in time is the Sublime.3

All of this is part of the history of the internet of course, and the internet does everything it can to stop you going back to remember what happened. You have to stay in the present. You have to stay right here. And you certainly aren’t allowed to stop.

.

Zachary German once had a zine and the name of this zine was The Name of This Band Is The Talking Heads. Zachary German could be said to have invented the modern podcast in 2014 with Every Time A Police Officer Gets Shot I Throw A Party, which he started to make after finishing his podcast called Shitty Youth which he started in 2010. Zachary German brought Shitty Youth back in the Trump years—it was another thing after the end—and sometimes he would talk about shit like Playboi Carti album drops and Playboi Carti saying he would drop and then not dropping and German seemed to understand better than anyone what the non-drop meant and be able to talk about it at length and this was in the Trump years, and German used to say ‘s/o’ a lot, sometimes the Trump Years episodes of Shitty Youth were just a list of graceful shoutouts to those who didn’t stop, because basically everyone is tired but some of us want to just stop and say thank you for the whole thing, because if you’re making things in the after, for the after, there’s a lot more after there—and you get to say how it is.

You get to say Thank You. And it’s sometimes not Cool. But that’s the Sublime.

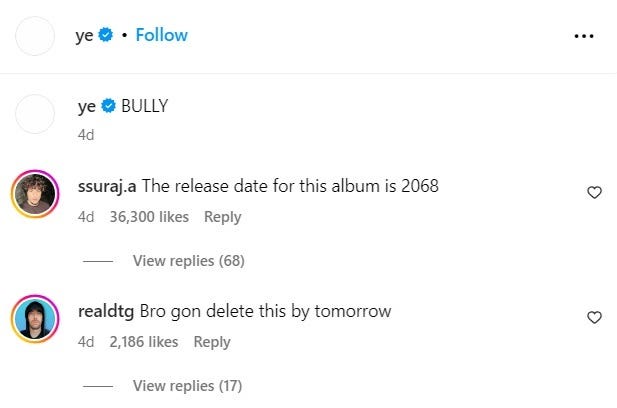

Ye does the same thing. I don’t understand much about the release schedule of Vultures but it’s like Ye is someone who wanted to stop and get out but he can’t, he’s not someone who can do that, because everything is framed now more than ever, it’s all idealogues and parasitism and, let’s face it, the new New York novel is a disgrace. Peter Vack sold out. Jordan Castro sold out. Honor Levy sold out. Matthew Davis sold out. Tao Lin sold out. Sierra Armor sold out. And, by now, Zachary German will have sold out.

—Here’s an excerpt from Shitty Youth 001, second season, Trump years, deleted and archived, in case you don’t know what I mean:

.

In Thank You from 2015 there is at least one extraordinary sentence,

I wrote something years ago about how in my finding routine activities so debasing I failed any longer to empathize with the urge to produce and consume artwork about what is conventionally deemed prurient.

Zachary German wrote that just as it is, ‘consume artwork’. A seeming infelicity that isn’t one. It’s a very simple sentence about something very hard to accept, or rather a slightly twisted-out-of-shape sentence about something very unbearable because once you get there you can’t go back and you will just stop.

You will stop identifying with the urge to ‘consume artwork’ and say thank you.

Sneak Beach says that both Ye and Carti ‘seem to understand its not really about the thing or releasing the thing but the aura cultivated around the thing’. And it’s also true that sometimes the words that break everyone’s hearts are the ones most adjusted to the giving in, and not so much the giving up. We find the dysfluency of those who have given up moving. And those who give in, sometimes more so. I like Ye’s pictures of Bianca and never listen to his new music, from which he said he retired. The thing that must make us stop and surely will is this other thing that broke so many hearts there was hardly a single word left, even for it, by now, fr.

And what do we really talk about in 2024 when we talk about selling out? When we say ‘sold out’ in 2024, we don’t mean what you think you understand by that. We don’t just mean the Penguin handlers of Honor Levy or Matthew Davis wanting to be declared the new Phillip Roth by Leo Lasdun or Peter Vack’s cuckcore Drake fanfic novella Silly Boy being a kind of hyper-niche version of Jeff Koon’s inflatable Rabbit. We don’t simply mean the cashing in, the compromise that is universal culture itself. We continue to mean something else.

A tone far more grateful, far more inscrutable. An impression.

1 Oct 2024, ty, s/o

Sort of riffing on Erik Stinson interview with Adam Humphreys here, where Tao Lin and Zachary German are taken as something like polar opposites of alt-lit. ‘No strategy vs. all strategy.’ Giving and a fuck and not giving a fuck.

He actually continued writing for a while after and then stopped—or appeared to.

Everyone (Hegel, Derrida, de Man, Warminski, Lyotard, Moten) have written about or pointed towards the inscrutable place the sublime has in Kant’s text: essentially the sublime cannot be found in an object. It’s an object for which there is no exemplary object.