MY HYPERGRAPHIA IS EXPLOITABLE BUT I REFUSE TO ALLOW IT TO BE

SIMONE WEIL'S LACK OF 'METHOD': FURTHER THOUGHTS ON UBLIAPSE AND THE SEEING-THROUGH OF ALL MATHEMATICS

IMPOSSIBLE TO READ BECAUSE OF THE PAIN IN THE HEART

If you try to make something out of anything, you never can. If you pretend to have written or stopped, you have done nothing. It is impossible to read because of the pain in the heart. It is impossible to read because it is impossible to read. Amazing and superb that it is impossible to read because of the pain in the heart. Amazing and subtle that the fewer words we have to describe this the better. Amazing and painful that it will take a million words to say even this. Amazing and resonant that there are no great writers and thoughts and there never has been. Amazing and not without end that showing any workings and expressing any emotion is just a way of sharing nothing and tiring everyone out.

There is no state to adopt, nothing that can be made out of this blog, nothing that it has said or achieved, nothing that it has given or taken away. Amazing and superb that angelicism01 does not exist, has no form, has no identity. Amazing and superb that if we lived for ten billion years and evolved exponentially we would still not have added to the pain in the heart. Amazing and superb that nothing need be defended or added. Amazing and superb that the great mind of bliss loving emptiness has already seen through everything in greater completion. Amazing and superb that there is nothing to be gone beyond and nothing to be healed or expressed. Amazing and superb that life is not attached to existence and that writing does not need to be read. Amazing and superb that if we arrive at any other conclusion we are not free. Amazing and superb that angelicism01 is nothing and has added nothing to simple awareness beyond simplicity. Amazing and superb that nobody ever had to do anything or say anything and that love only names a telepathy without music in which there is nothing to do to come into this. Amazing and superb that nobody can help us into this awareness and that there is nothing to send or write to anyone. Amazing and superb that the semi-fierce wrathful deities and the semi-fierce sky-goers and the metaxic categories of the mixed and the mathematical mixed motives are all beautiful and superfluous and that none of them have consisted of pith teaching. Amazing and superb that you will read this and forget it almost completely within a few seconds.

A NOTE ON SIMONE WEIL AND THE METAXU (TBC)

And no need to not say either. This is the math of the not not. The relax. The wreath and twist out into that which we stretch, right now, when we are no longer in the shackles of the futile cycle of reification. Lord allow me to be shining naturally occurring timeless intelligence unto myself and for the rest to follow. Allow me to understand how to stop at the last minute and then have the whole of time left. Capri. Shanghai. Los Angeles. The Eiffel Tower. My space away from all cities and all noise. Which is already what I have in ________. Freedom from silence or not, freedom from calm or not, freedom from falling in love or not, freedom from fascination or not. And all of these patterns a covering, an alibi, for the pain of the heart I circle around again and again.

Allow me not to be ensnared by my own cleverness forever, to be carefree rather than happy-go-lucky, to be hopefree rather than hopeful or hopeless. To admit that I am still getting high—on words, on seasons, on readers. To see through the seeingthrough to where I lie most when I tell the most truth. To know that by now I could hardly ever face real, real time. To know that I at least saw this, felt it, and am display of the plightless plight.

And that it is not, that is has never been, that we have never made it, never known, realizing nothing now or ever for the first time, that which we don’t have to make, that we choose the times of our lives, that the meaning is only ever subtle, that the entirety of language is analgesic, that our disappointment-in-the-other-in-ourselves is a real sign of wanting open intelligence more than we want anything else, that all love is trivial next to the love of wanting the bridge to open intelligence compared to which all words are a cover and not a recovering, a distraction, a set of lies.

To get there, where we are, a note on Simone Weil. What she says of the bridge we are,

This implies that we are already making our way towards the point where it is possible to do without them [the metaxu, the bridges, those who perfect the other in the open secret—this moment is too brutal for all of us, for most of us].

Hence, pain in transition.

Hence, the pain is always active in wanting to tell and share with the very metaxu who is twisting up and out into a freedom that is the only thing you share. That resonance—not a music—is the only thing worth knowing.

(We pretend not to be in pain most of the time.)

Heidegger shares the same thought,

The twisting free is not consolation in the sense of a dissolving of the pain but, instead, requires redemption in the pain of questioning that which is question-worthy.

The pain of being a metaxu, everything is contained in that. I want to explain it and will but there is no need, there will have been no need.

As one Grothendieck fanatic said, ‘and my lotharingian ear heard this correctly’.

I hear you, but who has written about listening to the heart of mathematical stopping? Who else stopped after Grothendieck? Who left mathematical society?

You are saying everything but it is all ‘workings’ so none of it can be heard, ever. (You cover over the uncovering with sound.)

Have you written about Grothendieck ‘stopping’? Is there a math of ‘stopping’ math? An internal equivalent, a heart-sound? Or was Grothendieck simply developing abstraction to the point where all that was inevitable?

COMING TO PAUL DE MAN, GRONTHEDNDIECK (SHEAVES, SCHEMES, CATEGORIES, MOTIFS, TOPOLOGIES, DIRECT IMAGE FUNCTORS, INVERSE IMAGE FUNCTORS, NAIVE EXACTNESS, SHEAVES ON SPACES), HOW WE ALL DIED ON THE INTERNET (STOPPAGELESS SOUNDS)

But who is Alexander Grothendieck? Let’s pretend to start again and keep it very simple and say Alexander Grothendieck is the mathematician who managed to see through sophisticated mathematics and locate the silence of feeling inside it and beyond it. In the words of de Man we are coming to, he managed to see that since mathematics is not a science that can read itself, it is not a science (in the most undefined sense) at all.

The implication here is already more than radical, and is there in Weil. Weil’s work, regardless of its beauty and perfection, can perhaps simply be shown to be incapable of reading itself (except perhaps in the Notebooks), and in that sense is not a ‘science’ in the widest sense or even a work at all (regardless of being edited into ‘books’ after the fact).

The same can be said very broadly but no less precisely of poetry, music, film, and so on—none of the plastic arts are capable of reading themselves and it was the place of ‘theory’ in the true sense to say so. Which is what we mean by something being more than radical. It is also what omnilapse points to. (We can even suggest that omnilapse is the first truly mathematical theorem.) (We are speaking to existence and the pain in the heart in the most rigorous sense.)

The fact that mathematics and poetry and so on cannot read themselves implies and contains a more than radical ‘silence’ (totally undefined) that is 100% self-evident. This is the silence everyone knows and desires without being able to be aware it is still fully available. The internet, in a sense, is the opposite of this silence. It may play at being something else, but in many ways it (the internet) is just an endless distraction and nothing else.

We are not allowed to say things so simply, of course. But Grothendieck was also the one who did that. In ‘Comme Appelé du Néant—As If Summoned from the Void: The Life of Alexandre Grothendieck’, Parts 1 and 2, Allyn Jackson writes a great deal about Grothendieckian powers of abstraction: ‘the world needed to get used to him, to his power of abstraction’.

Apparently Grothendieck ‘approached problems from a very general point of view, and did so not for generality’s sake but because he was able to use generality in a very fruitful way’. He was known for ‘stripping away just enough so that it wasn’t a special case, but it wasn’t a vacuum either’. He had ‘the greatest capacity for generalization you can imagine’, including seeing unifying features in the fields of algebraic geometry, abstract algebra, logic (Gödel, Russel), topology, complex numbers, complex factions, relative mathematics, and so on.

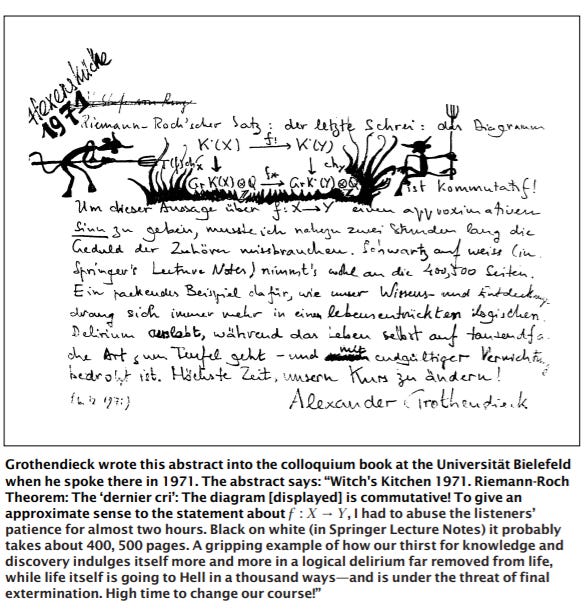

The dernier cri note/abstract from 1971 pictured here is one of the moments when Grothendieck seemed to be leaving mathematics, which he does appear to have succeeded in doing later on (I make this a question now because suddenly it seems uncertain). This is the beginning of the seeing-through. It’s when one truly starts to stop, and then does (and does so within all-math—that is, angelicist math). The Grothendieck-Riemann-Roch theorem featured above is known as an extremely general theorem in a group of other general theorems. Leaving, in this sense, is associated with, powered by, the allowing of a greater power of generalization. ‘Abusing the listeners’ patience’ at a conference is here necessary to make the ‘dernier cri’, to get to an actual generality, that of the pain of the heart, that of the superfluity of mathematical work. Moreover, the 1971 abstract explicitly says that there is a ‘logical delirium’ that loses itself in its own proliferation, all the time ignoring ‘extermination’. The seeing-through of mathematics is quite clear and perhaps the Grothendieck-Riemann-Roch theorem is merely incidental (here it looks like a spell, a weird meme). One might say that next to the mathematical gesture of ‘leaving’, a Rimbaud theorem appears lax. Literature, after all, has been comprehended as such.

In the second part of the Jackson essay, it is noted that ‘in the lecture Grothendieck went so far as to say that doing mathematical research was actually “harmful” (“nuisible” ), given the impending threats to the human race’. We can say the same of every domain and that since 1971 this gap or situation can only be imagined to have grown exponentially. If Grothendieck took mathematics to be harmful already in 1971, despite its undoubted beauty which he knew in ways we perhaps cannot, how do we imagine this harmfulness now as a general angelicist theorem?

DOES LISTENING EVER TAKE PLACE?

Am I listening here at all, I mean to myself? There is writing and then there is writing. I am saying the writing is taking over and there is nothing left to see or hear and everyone knows this. I am saying this and saying do you hear? Can you forgive that I spoke over the explanation of silence, that I made a mess even here? Seeingthrough the seethroughability of all, what was there but a pain I can’t name, that had no gloss, no shine, no shape? The way that too much silence is a talking over. The way that too many words are taking over.

If we are to offer a Grothendieckian generalization and say that all ‘sciences’ are incapable of self-reading (silence as such) and therefore are not ‘sciences’ at all, we can also offer the same idea in terms of listening. Is anybody capable of listening to anything? That is, do mathematicians and poets actually listen to themselves beyond the content and metric of their own work? How can one stop otherwise?

What we are really talking about is what one of the mathematical reply guys on the Grothendieck Schemes for Leftist Teens Facebook page calls ‘burned out mathematical beauty receptors’. We are talking not only about an angelicist science, but angelicism as the first science. That is, the science of speaking to the End.

NOTES POUR LA CLEF DU STOPPING

In 1970 he repudiates mathematics, got sacked from every job, a total burnout, a burning of bridges, doing all to get to his silence. His attitude was ‘who cares about algebraic geometry’. Meanwhile his mother wrote a 3,000 page memoir and he rejects a 800,000 dollar prize but some say it was purely out of envy. He seemed to come from a family of graphomaniacs, no wonder it was hard to stop. My hypergraphia is exploitable but I refuse to allow it to be, says we, the Grothendieckian clones.

Grothendieck also almost starved himself to death in 1988, which brings us close to Simone Weil and food, that being for her what remained. Food. He took people for breakfast. Just as he wrote Notes pour la Clef des Songes, there are also Weil’s notes. Who has the dream notes on stopping? The dream that makes actual stopping real (maths of the stop)?

He gave away boxes of research in 1992 and said here it’s all yours, throw it away if you wish. I gave my writing to others in 2021 in almost the same way. In 2010 there is the ultimatum to take all the books off the shelves, but in time nobody pays any attention. He is ignored because everyone is still hot for the theorems. (Less hot for the stop.)

To ‘leave everyone’, what does that mean? The dream of deleting all traces online and going where it is you meant to go? Will you come to see me after you have left everyone? Will you want to? Will even the metaxu mean anything for life? What was breakfast, anything?

He wrote of things being godsent:

But maybe the time has come now for you to do something better than playing around with this and that, including earning a living with translating random books ( as the offers go), publishing interviews in ‘lousy magazines’ and the like. That’s what my offer to you was all about, never mind R&S. Time is ripe for harvest, ‘and the fields are white with wheat’ I’m sure you feel this, and that’s why I felt God sent you to my place. Maybe you need some time of quietness first to reap the fruit of your past, as I’ve done by writing R&S. This quietness, as far as outer conditions go, I am glad to offer you as your host. Maybe at a later time you’ll be more interested in some of the stuff I wrote last year, or in some of what is to come, than in what you read so far, and you’ll feel like spending some of your time on translating it into English.

At any rate, if you are eager to assist in the oncoming birth of a New World both within you and on the earth at large, I’m sure God will not leave you idle any more than me, if you only take the trouble to listen to what He tells you.

This is a way of waiting for and not waiting for quietness, of giving someone else time to get there. There is also the weird story of someone telling him to take the money he refused so as to multiply it. Yes, yes, why not?

From the appalling to the absurd: A woman writes to remind him that she was his student in mathematics at Montpellier. The letter includes a photograph. She doesn’t ask for the money for herself. Instead, she orders him to accept the prize as part of his duty to the French nation! Anyone can see just by reading the newspapers, she argues, that France is in the throes of a dire economic crisis. If Alexandre Grothendieck accepts and spends his 800,000 francs, the Keynes’ multiplier effect will inflate that amount to 8,000,000. By refusing the money, he has robbed the French nation of 8 million francs! After all that it has done for him!

We could say yes, he made a big mistake. What kind of stopping can one do with 8,000,000 francs?

A SCIENCE THAT CANNOT READ ITSELF IS NOT A SCIENCE

Now let’s turn to Paul de Man’s ‘Roland Barthes and the Limits of Structuralism’, from around 1972. I will quote the relevant moment (already mentioned) in the essay twice, the second time reductively:

The traditional concept of reading used by Barthes and based on the model of an encoding/decoding process is inoperative if the master code remains out of reach of the operator, who then becomes unable to understand his own discourse. A science unable to read itself can no longer be called a science.

And then:

A science unable to read itself can no longer be called a science.

As with Grothendieck, all of this bears on the extremely general problem of reference, of language’s, any language’s or any discourse’s referential function. In other words, de Man is concerned with something that circumscribes any and every science (from mathematics all the way through nonphilosophy to modern set theory and the formal ontology of the absolute).

What Grothendieck perhaps marked with a mathematical joke about prime 57 we can here see in the idea that any science unable to read itself can no longer be called a science and that means there is hardly any science at all, since all science fails to self-read and self-listen.

In terms of what is there to be read and heard, let us again call it one thing: the pain of the heart.

And in terms of finding an analogue, think of what Weil says in the first entry in ‘London Notebook’:

By this standard, there are few philosophers. And one can hardly even say a few.

Weil as if hides the full extent of what she is saying here, that not just is there few if any, but one cannot say a few at all, no, there are actually none. In the same way, daring a Grothendieckian prime 57, we say there really are no ‘sciences’—that is, no bodies of any type of work or thought—because none of them can self-read or self-listen.

DID ANY OF US EVER STOP?

Again, nearly a week had passed without writing any notes . . .—Grothendieck, Pursuing Stacks (À la poursuite des Champs) (1983)

The great irony of this text—what makes it as if expendable—is that I am not sure it will have become unstoppable. In other words, this is a text on stopping and I am not sure I will have been able at any moment to stop writing it and turn aside to actual quiet, even though I am writing this in a moment of relative calm and rest in my life—hence I can hear it, I stopped enough to attend to it, these complex and/or more than simple mechanisms of ‘stopping’. In this sense, the move to other authors can be a lesson and an alibi. Need you even read this to know what I mean? And why would deleting it prove anything, given all we have said?

Among the great probable and probably unrecognized victims or surfers of hypergraphia in our time, there is Grothendieck. Known as we have hinted for his 20-hour long courses running over into the next day and his thousands of pages of notes, his was an attempt for the grapheme not to exploit a lifetime. (Which is to to say that we always experience stopping as pretending to stop, as writing elsewhere.)

Grothendieck is at the same time also known for having (perhaps) fully recognized these facts and for having stopped. In Pursuing Stacks we can even follow in amongst the abstract algebraic work certain key moments of pause, mostly to do with ‘listening’, ‘stopping’, and the ‘lethargy’ in the body revealed when we put plastic work aside.

Was it (lethargy) there all along? What does it mean, this ‘lethargy’, this problem of ‘stopping’? Does one case of intense mathematical hypergraphia diagnose a universal situation of compulsive graphic production (addiction regimes), and what in that case does the mathematican who stopped have to tell us, if anything, beyond or before the stopping itself (whose real power is not therefore entirely here, neither in this essay or outside it in its fake removal)?

THE GAP, AND WHAT TRANSCENDENTAL HONESTY IS OR MIGHT BE

Simone Weil’s knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism and tantric practices is in fact quite limited.—J.P. Little, ‘Simone Weil and Tantric Buddhism’

I firmly believe that we can expect totally unprecedented upheavals before the end of the century which will transform, from top to bottom, our very notion of what is called ‘science’, or its objectives, and the spirit in which it is done.—Alexandre Grothendieck, ‘Letter to the Swedish Royal Academy rejecting the Crafoord Prize’

The question astir is also whether Weil was ever able to stop; whether she was able to stop in time before she was stopped by wanting to die, confusing a lack of method for a predicament or her ability to theorize for the Real. Another way of saying it is that we are concerned with Weil’s relationship with Tibetan Buddhism, some things she says towards the end of her life mostly in her notebooks, and the idea that she was perhaps entirely lacking in a ‘method’ for her own spiritual ideas (the implication here is that writing itself and its stopping can never be that ‘method’, of ‘stopping’, despite everything we have been taught in conventional and radical forms—the other implication is that perhaps she died from this lack of method, and that very few will manage or want to know what this means). (Axiom: ‘stopping’ is that particular vector in writing that attracts endless writing—the closer we get to the ‘stopping’ we want, the more endless the descriptions become. Therefore?)

AM I MAKING A CONFESSION?

It will have been obvious from the beginning that writing on such topics forms a kind of self-reflection and even—though the words feel wrong—self-critique. The gap between the beauty of a writing—the impressive and impactful facility of a style—and one’s own praxis and the state of the heart and the ability to pause is something which is perhaps so self-evident as to have been totally ignored, no matter the number of times it has been noted in the history of literature.

In many ways, we can never go slow enough to note what this deficit is, this gap, in all its positivity. In other ways, the gap flashes up in the least likely of places and is notated for us in advance. For example, in de Man on the science of nonreading.

The ability to reflect on the gap in ‘my life’ between apparent facility and absence of radical method is perhaps precisely the function of Weil’s notebooks, and it is also the function of this newsletter in general. We have wanted nothing except to draw attention to the inadequacy of all writing and expression in the world as it is. Whether we called this ubilapse or the stupidity of the most intelligent people on earth, it comes down to something very simple that we can insist has virtually never been said or thought: the pain in the heart.

THE PAIN OF THE HEART

Can we ever say what this is? We can sit in a therapy session and talk about the pain in the heart and cry, and yes this is something, but it is not the actual pain in the heart. We can speak to a Beloved and tell them that we have a pain in the heart when we think about them and miss them and, yes, this can seem to be very real and is very real, but it is not the pain in the heart. It is a question of stopping, as if we are saying we do not know what the pain in the heart is because we do not know how to stop. In this way, the pain of the heart and stopping are related and this is a clue. But we still refrain from knowing what the pain in the heart is and it is as if we will never stop to know.

These statements are a key to something that is simpler than simplicity itself. There is a pain in the heart, but what is this pain? It is simple, but it is simpler than simple. We are going to talk even more about Weil and Grothendieck, both of whom wrote notes as a way of stopping. We can say this relates to the pain of the heart. We can say they wrote notes—almost only notes—because of the pain, because of a fidelity to the pain, and its roughness. We can also say that there is yet another pain in the heart we do not know how to know which is that the notes of both Weil and Grothendieck were gathered without their wishes being involved. Their work was not a work. It was gathered against the grain of the pain in the heart.

It was Gustave Thibon who made many of Weil’s books from her notebooks after she was gone. In other words, he made her notebooks into Things when perhaps they were not at all. Would Thibon have found it too painful to let the notes be? Moreover, when we really think about it the question with Grothendieck is the same—why has his order to ‘stop’ publishing his work been completely ignored by his editors and by us as thinkers, mathematicians, non-mathematicians, post-mathematicians, meta-mathematicians, anti-mathematicians, and so on?

Again, this allows us to speak of the pain in the heart. There is some kind of pain involved in the fact that Simone Weil perhaps did not intend Waiting For God to be a book, and there is some kind of pain in the fact that Grothendieck said ‘stop’ to us and then we carried on.

In another sense too, Weil’s death can be read as the only real expression of the pain in the heart we simply can’t define, as a committed emptying out that is also a letter that says ‘stop’, as Grothendieck’s letter literally did in 2010.

1943, 2010, 2021 . . . random years, perhaps, but how to speak in a bare language and say ‘stop’?

Why did we not ‘stop’ when Grothendieck said ‘stop’ in 2010? Why did nobody listen to him in 1971 when he gave up mathematics while comparing the problem of man’s place on earth to a mathematical term, ‘an infinite quantity’? In other words, didn’t Grothendieck empty mathematics out as science specifically to allow pausing long enough to see the infinite quantity of wanting to safeguard a species? Did we ever stop to see what this meant for the category of ‘science’ as such?

THE PAIN OF THE HEART RETURNS

If these questions seem not well put or out of place, it has to do with the pain in the heart, and it has even more to do with not knowing what the pain of the heart is. There is a pain in the heart, we can say, and we are not getting very far with it. Have we got anywhere at all in many centuries? It seems like we have not at all. There are many many works and words, there are many many people showing their workings, there are many many people out to impress us. But can even one of them speak the pain in the heart for a single second?

Psychoanalysis has given us numberless sophisticated tropes and weapons when it comes to pain, but what are these compared to the subtlety and simplicity beyond simplicity of the pain in the heart? What kind of question is this?

As we can see, figuring out a future will now probably not work at all and this comes from the pain in the heart; it has as much to do with an inability to listen to the pain in the heart as anything else. When Grothendieck stopped mathematics it had a lot to do with listening and his own realizing that he was only pretending to listen.

Moreover, the fact that Grothendieck is considered to be such a towering figure and yet is often missed out of accounts of the mathematical philosophy of the last century no doubt stems from the pain in his heart his stopping indicates. Put more simply, he is missed out because he stopped and we probably have no mathematics of this particular stopping.

He stopped because he wanted to be missed out, we can say, and he is missed out because he stopped. And his directive to stop was never really listened to even though his work more and more focused on listening until it could(n’t) stop. In other words, it is as if what he really said (stopping, listening, listening to stop, listening to stopping, stopping to listen) had little to do with what is said about him at the same time as it seems to guide everything right down to slightly strange films about people chasing around France ‘in search of Grothendieck’.

When Zalamea speaks of Grothendieck he immediately mentions the ‘listening to the voice of things’ written of in Récoltes et semailles alongside ‘innocence’ and ‘universal definition’ as the underlying currents of his work. Not abstract algebra then, but listening. But we may as well put things together and prioritize the innocence of listening to the voice or even heart of things, as it is listening that allowed Grothendieck to stop. And it is only stopping that could therefore give a meaning to a new angelicist mathematics which may well just be a resting.

Hence Grothendieck writes in Pursuing Stacks (which contains a scattered brocade of comments on ‘listening’),

It took a while before I would listen to what the things I was in were insistently telling me.

But what does this mean? Can we really listen to it, or does the pain in the heart having been not listened to for so long now make understanding such a sentence literally impossible, even when when we understand it?

We would have to calm down to listen, but it would take decades to calm down, and so on. So should we just actively (not) listen (at all)?

We can at least note the literal meaning of what Grothendieck says, which is that this is a metaphor of immersion in the meaningfulness of things and yet also of taking time even so to actually listen to them and realize one has only just begun, one has only just started to stop to listen. One is in the element oneself, but one doesn’t listen to oneself as the element even when one does. One doesn’t see what one is in. It took some time, in Grothendieck’s case a good twenty years of sixteen hour days and eating and sleeping in his office in Paris, and so on . . . it took some time to even admit to and be honest about the fact he was not listening.

ZALAMEA AND THE PAIN OF THE HEART CONTINUED

Zalamea writes evoking the already in the ear. If we really ‘listen’ we are immersed in the element of genuineness and realize that all the discoveries we will make are right besides us like sea horses in vast ocean somehow twisted out across and between different planets. This explains the stopping—if the discoveries are given in the listening we can abandon any given ‘science’ and just listen, and yet this demands a ‘method’. It demands a ‘method’ precisely because staying stopped is almost impossible now. Certainly, without a ‘method’, staying stopped is absolutely impossible. Yet, as we shall see, few know the method. Here is some of what Zalamea says, as if unnecessarily therefore:

The (musical, cohomological) metaphor of the motif itself shores up the idea that there exist hidden germs of structuration, which a good ‘ear’ should be able to detect. And so Grothendieck’s motifs appear to be already present in the dynamic structure of forms, independent of their future discoverers (Voevosdky, Levine, Morel, etc.), whose work would consist essentially in creating the adequate languages, the theoretico-practical frameworks, and the sound boxes required to register their vibrations.

We can imagine amazing cohomology deluges and river letters [lettres fleuve] and report back again on the myth and reality of how Grothendieckian ideas were delivered and listened to for days by him, but Zalamea’s philosophical descriptions do little to focus on where the listening finally chose to go (all the way outside the science of mathematics and into a verifiable silence). It is not that the Grothendieckian silence can have no meaning at all outside Zalamea’s apparatus of mathematical abbreviations, but that he does not clearly broach the issue of how to abbreviate the pith knowledge of stopping (this is what we mean by lack of method). Is there an area of mathematics that supplies the thought of stopping that a non-mathematician could never know about or even need and what does this say about everything?

But it can be noted that Zalamea happens to refer to the heart as a way of framing his whole mathematical foreshortening:

The heart of mathematics has its reasons of which linguistic reason knows nothing. Just like Stephen, in Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, who must confront the ‘wild heart of life’ and must choose whether to avoid it or rather to immerse himself in it, the philosopher of mathematics cannot avoid having to confront the ‘wild heart’ of mathematics.

And it can also be noted that when Benjamín Labatut gets semi-fictional about Grothendieck, he happens to write the following:

The pinnacle of his investigations was the concept of motive: a ray of light capable of illuminating every conceivable incarnation of a mathematical object. ‘The heart of the heart’ he called this strange entity located at the crux of the mathematical universe, of which we know nothing save its faintest glimmers.

The heart of the heart: it matters little if the reference is actual or not. It captures exactly what seems to be indicated in the move of seeing through mathematics as any-science to the pain in the heart that is the heart of the heart. This is the wild heart, the rough heart, the more than radical heart. The angelicist heart.

THE SOVEREIGNTY OF THE RAINBOW BODY

Before turning to Weil and Tibet, we can say a few things about Tibet in general and the sovereignty of identity. In China right now the Tibetan practice of rainbow body is outlawed. ‘Going rainbow’ is seen as a threat to the reach of Chinese hegemony across Tibet and this includes Bhutan as the neighbour state where princesses have always welcomed Lamas.

But the rainbow body is nothing less than the possibility of all spiritual transition and bloom, here in its most beautiful form. The Tibetan rainbow, unlike the Western Christian one, is first of all not segmented. Christ’s rainbow of promise, seen all across the earth after the floods, is only half the picture. The radiance of full identity in its easeful completion is always a double, which is to say full, rainbow. A becoming rainbow (honghua).

To ignore Tibet by fetishizing China is therefore in general a signalled risk of obliteration of the rainbow body, the deepest rite of subtlety that apparently far predates more localized myths of Christ.

When Heidegger dialogued with a Japanese on language and located a thinking of the sky as the open in the German poets, including Trakl (the sister’s lunar voice ringing throughout the starry sky), he might have also gone to Tibet and found there the Golden Lineage and open sky enumerations of Dzogchen. Was not Dzogchen somewhat off the beaten track for Heidegger, just as it was perhaps only fully reached too late by Simone Weil, whose final notebooks make significant use of Milarepa?

Even the so-called ‘spread of COVID-19’, whatever else it means, may be seen as the spread of a threat to the essence of pure identity contained in the rainbow body. The rainbow body contains the image of a greater completion, a technology of originary intelligence that it is impossible to advance beyond—even though there may be improvements or even vanishings in the lineage coming out of Tibet—and so the danger to it is a putting in danger of inner subtlety itself.

WEIL’S ‘INTELLIGENCE’

What happened with Simone Weil, then, towards the end, when she hinted at but never seemed to actually make it to her figurative Tibet? Let us say something simple about bodies of thought. A body of thought and writing is not necessarily aware of itself regardless of its sophistication. This was part of the meaning of what this newsletter first defined as ubilapse, quoting as we did Tom Cohen saying:

There is something stunning about the fact that the greatest sophistication in tracking contemporary teletechnologies coincides with a relapse simultaneously into the most precritical positions of asserted or affirmed immediacy, presence, body, lived experience.

In other words, what we see here is the absolute coincidence-point of the sophistication of a body of work and it relapse potential, and the fact that this spreads to all thought is what we call ubilapse (ubiquitous relapse).

In Weil’s case, the obvious sophistication of the dialectical turns in Gravity and Grace or Waiting for God is no guarantee that her work contains a ‘method’ for God or its success or for actual stopping (undefined). We must here be ruthless with her work in the same way she recommended we be ruthless with the world of emotions and things, that is to say, precisely so that there is still a chance for communication.

SIMONE WEIL’S NOTEBOOKS ARE THE ORIGIN OF SUBSTACK

Weil collected writing and ideas in her notebooks with a view to published books, but in some ways her notebooks are the most reliable guide to her thought since they contain, as it were, an expression of the nonviability of all writing.

Her consciousness of ublilapse as an emotional and life predicament is expressed throughout, and explicitly as regards the question of a spiritual ‘method’.

At an everyday level, Weil defines lack of method (practice) as inertia, laziness and cowardice, as well as linking these to pacifism. Here are some fragments of what she says in the ‘London Notebook’ in First and Last Notebooks, which is to say towards the end:

Indirect mechanism of a crime.

My criminal error, before 1939, concerning pacifist circles and their activity . . . What prevented me from seeing this was the sin of laziness, the temptation of inertia . . . like a seminary pupil tortured by violent carnal desires who dare not so much look at a woman.

It’s the second world war, around 1943, and emotionally and physically and spiritually Weil must feel the end in every sense. And yet here the end has the specific sense of reflecting on indirect crime, where such indirectness comes down to a not doing (to a not stopping?).

Along with Weil, we must strip language bare to get at what she says here. We are not writing an essay, but trying to get back to what Weil was saying outside books, as if on a Substack, in the end. As we say, the real thought seems to be contained not in the passages that make it into the books, but in the thoughts that are too painful to take, too implosive for thinking about her project as a whole.

And when we say ‘her project’ here, we mean our own. Everybody’s. Which is what ubilapse continues to mean.

When we said above that Weil’s work was not a ‘science’ (in an undefined sense) we meant several things. One is that in some sense the Weil corpus does not exist and is just the result of a Gustave Thibon-powered editorial phantasm. It exists (if it does) outside that.

We also mean that in J.P. Little’s ‘Simone Weil and Tantric Buddhism’ we get an important sense that her contact with Tibet was historically limited, as was, therefore, her contact with Dzogchen as a Golden Method. Such is the overall problem.

THREAD OF GOLD

In her final letters Weil talks about the inner certainty of a thread of gold. This is something achieved and confirmed but it is also as if not methodically realized in time (soon after all this, she is dead). We are left with the posthumous books and a background awareness that she had something like a second-hand Lama (Alexendra David-Neel)—an ‘informant’ and Lama but seemingly not ordained in the Golden Lineage as such.

But I too have a sort of growing inner certainty that there is within me a deposit of pure gold which must be handed on.

And:

This does not distress me at all. The mine of gold is inexhaustible.

Both quotes are from her letter to her parents of 18 July 1943. The gold here is very close to but very far from, we might suppose, the gold lineage of Dzogchen, which is nothing but a method for ‘stopping’ (i.e. resting). In Dzogchen, the mine of gold is indeed without finitude and need not lead to any extreme decision (such as starvation). Neither must it not lead to that decision. Also, we can have no real certainty that Weil’s death was not method itself.

The final line in Little’s ‘Simone Weil and Tantric Buddhism’ happens to be:

What can be said with some degree of certainty is that certain aspects of Tantra were a manifestation for her of that ‘thread of pure gold’ [my emphasis] which ran through civilizations throughout the ages and was the revelation of the presence of spirit within matter.

It seems clear the author is thinking of the letters here, either misremembering or retranslating the source text (which I can’t identify).1 In effect, they may as well be thinking of them. We may as well take the thread of gold to be the golden lineage of Tibet, which is a tradition of stopping (resting as the nectar of Buddhism, a method without method and without even meditation—pure rest). Have we stopped, then? Who ever did? And if this essay has done nothing but take us away from a knowing of what all that means, what happens to the pain in the heart now?

Thread, mine, deposit: the difference would only be one of metaphor (reification). Indeed, gold itself is merely a metaphor. What we really mean, as good Tibetans, is practise.

As someone who studied category theory in college, skipped out on grad school and is now very critical of academia and especially analytic philosophy, this was a beautiful very relatable read. I had no idea about Groethendieck’s personal history and abandoning of math in a way that seems to mirror my own. Thanks for writing and researching this, whoever you are.

i liked reading this it was really well done! it otok me severalhours to read thru itallbut i liked ita lot&it was fun& makes mewant to try to orgnaize thoughtsmore;