SEXUAL MEMORY AND THE INFINITIES

R.I.P. Pierre Joris.

When I make love to you I always want it to last forever, to be as infinite as possible, but I also always want the end to come, and to have it with you. The ends of sex are themselves (infinitely) finite.

Sex locates for us a truly immanent theory of infinities.

Another way of saying this is to say that sex is related to memory, but also that sex threatens to put a stop to memory. Sexual memory is necessarily finite because the sexual act does not usually last, as act, into sexual memorization itself. Sex is, erotogenically, coded as loss.

No matter how good our fucking is, and no matter how imprinted our immediate memories of what it means to make love, memory distinguishes itself from remembered act.

In truth, ‘sex’ is not fucking at all, in a strict sense, but the domain (sex-memory-loss as dissolution, or, ‘Platonic love’) in which physical acts of lovemaking place themselves.

Sex must be the immediate experience and proof of what is infinitely finite, of that which moves the theory of sets towards the point of its own end (‘orgasm’, ‘stopping’).

When I fuck you I want it to last as long as possible but in order to do just that it has to end. When I fuck you I want by definition to be inside you as long as possible but even if I achieve that, we both still want the end as ending, we both still want to come—we want the end to come.

.

Sexual experience and memory therefore present a tightly bound dialectic of infinite and finite. Orgasm is coming (to an end). In some ways, much of what we wish to know about set theory and the higher infinities may be learnt from sex: sex here naming the conflation of the ontology of a sexual zone and the appearance of a physical act, a beatmatch between what Frank Ruda’s essay ‘To The End: Exposing the Absolute’ has called meta-ontology and objective meta-phenomenology.1

Kurt Cobain once described his wife Courtney Love as ‘the best fuck in the world’ and if we fuck Love as Cobain did, or rather Cobain as Love did, then we find the miracle of the ‘penetration’ of the absolute into the singularity of a sexual world.

Yet, since sex has no memory, or none that is actually tangible, the miracle-infinity of sex is immediately written back into previous (thereby finite) large infinities; into the fragile crucible of sexual genealogy. Over time and pretty soon the best sex in the world is subject to ‘reflection’. After we fuck we can always fuck again, we can always create more infinites, but the very need to do so means the best fuck in the world has been virtually left behind—inscribed, written, raised up, now once again to come.

In effect, this translates as: I am not fucking you right now. And: since I am not fucking you right now, reading has replaced sexuation and fabular genealogy, and artificial intellectuation has surged into priority, whether we like it or know it or not. There is only the infinitely finite fucking now.

*

Insofar as the sexual infinities (penetration of the absolute into a sexual world) are something that can really take place, they must be finitized after—and during—the fact. Memoryless sex is the actually infinite experience of the becoming-finite of the infinitely finite.

*

Though the meta-phenomenology of sex is distinct from the absolute formal ontology of sexual memorization, the two also run parallel. Remembering sex makes us confront the difference between the infinite potentiality of the act (generation) and the potential, finite act of its total recall (quietness, fantasy), thereby releasing us to, surprisingly, experience infinity again, namely the infinity that separates the two sides of any choice. Adopting Ruda’s language in ‘To The End: Exposing the Absolute’, sexual forcing takes on the unique color of forcing us to force a fiction of choice: total recall and/or an immediately new axiom of eros.2 Where Ruda writes that we can force an absolute ontology, we may also force the memory of the 滲み出るエロ(sexual ooze) that attaches to ‘angelicism01’ as a second name. Ultimately sex recalls for us the inscription of an impossible preference for the (absolutely) large that itself settles on this side of a kind of indestructible minimalism of hope (make bigness hope), opening out the spaces of the absolute, confirming also as it does ‘the marvelous partly unconscious sureness of mathematical names’.3

Sex proves that the infinities themselves are infinitely finite, that they disband themselves according to a law of generation and loss already hinted at in The Immanence of Truths as ‘a secret finitude of the absolute itself’4 but perhaps best located by Ruda himself, writing a kind of meta-logic of Badiou’s unconscious results, as what he calls ‘the end of infinity’, and formalized in this sentence, which is as if more precious than the entirety of Badiou’s project:

In the end, what the thinking of actual infinity ontologically and meta-ontologically necessitates is an emancipatory theory of the end.5

Several ends, then. As with sex. In sexual fabulation (quiet, even idle fantasy) there is always the question of an exasperated teleology, of what the end has to say about the end of endlessness as always-necessarily-possible, as immanent in other words, more primarily immanent than any supposed stability of ongoing ‘eternal truths’. In an interesting footnote to ‘To The End: Exposing the Absolute’, Ruda will indeed anticipate the end of his own essay, as he does several times, by writing that,

The solution, as I will only be able to indicate briefly at the end, will lie in splitting the concept of the end into two. One divides into two: even at and in the end.6

While Ruda as a reader of Badiou seems in part to be asking what happens if the end of set theory is just the beginning of a new ontological framework and event, it also seems to be the case that if the potential failure of set theory, its end in that more boring sense of the word, is here ‘exposed’, we come back into the physics of an interrupted teleology. The solution to the problem of mathematical ‘reflection’—the integration of any new infinity in those preceding, their writing-back—is here found in a splitting, in a need of multiple ends.7 In the end, Ruda will find himself saying, the theory of the end is what we find at the end of set theory and we find this, in and at the end, at the end of the infinite, and this fails to have nothing to do with the fact Badiou chose to write out an absolute formal ontology during a specifically finite moment, a moment in history of perhaps bewilderingly unique infinitely finite finitude. While Ruda does not quite explicitly put it that way, it is hard in the end not to follow the clues.

*

In a recently translated and published text called ‘The Notion of the World’, a very young Derrida points out that the finite/infinite dynamic that has been a central part (Kant’s ‘crux philosophorum’ or secret cross) of the modern history of philosophy ‘has a Christian origin’.8 What suddenly becomes easier to understand following this reading is the difficulty Badiou often seems to have with divesting the domain of the absolute of the finite traces of the world it also has to locate its working instances in, its ‘works’ which are always to be distinguished from, essentially, pieces of shit, the déchet, the waste item. Though the absolute finds itself only in a finite work, and therefore the infinite only in the finite, Badiou fails to explain how just that fact brings back into play precisely the shit in the domain of the finite he wishes to jettison in favor of patently (despite his denials to the contrary) Christian eternal truths. Isn’t it entirely self-evident that Badiou is rashly confident that he can unproblematically detach the ‘essential content’ from metaphysical and Christian sources and continue to use the same vocabulary without detriment to his thinking, especially when the finite-infinite friction is itself a secretly Kantian crux (cross) of traditional philosophy? Remembering sex again, where eternal truths are never quite that, and this is their irony, their joy, their frisson, their story, their sound, their changing of place. ‘Oh fuck, ‘oh god’: these are words we are yet to completely understand.

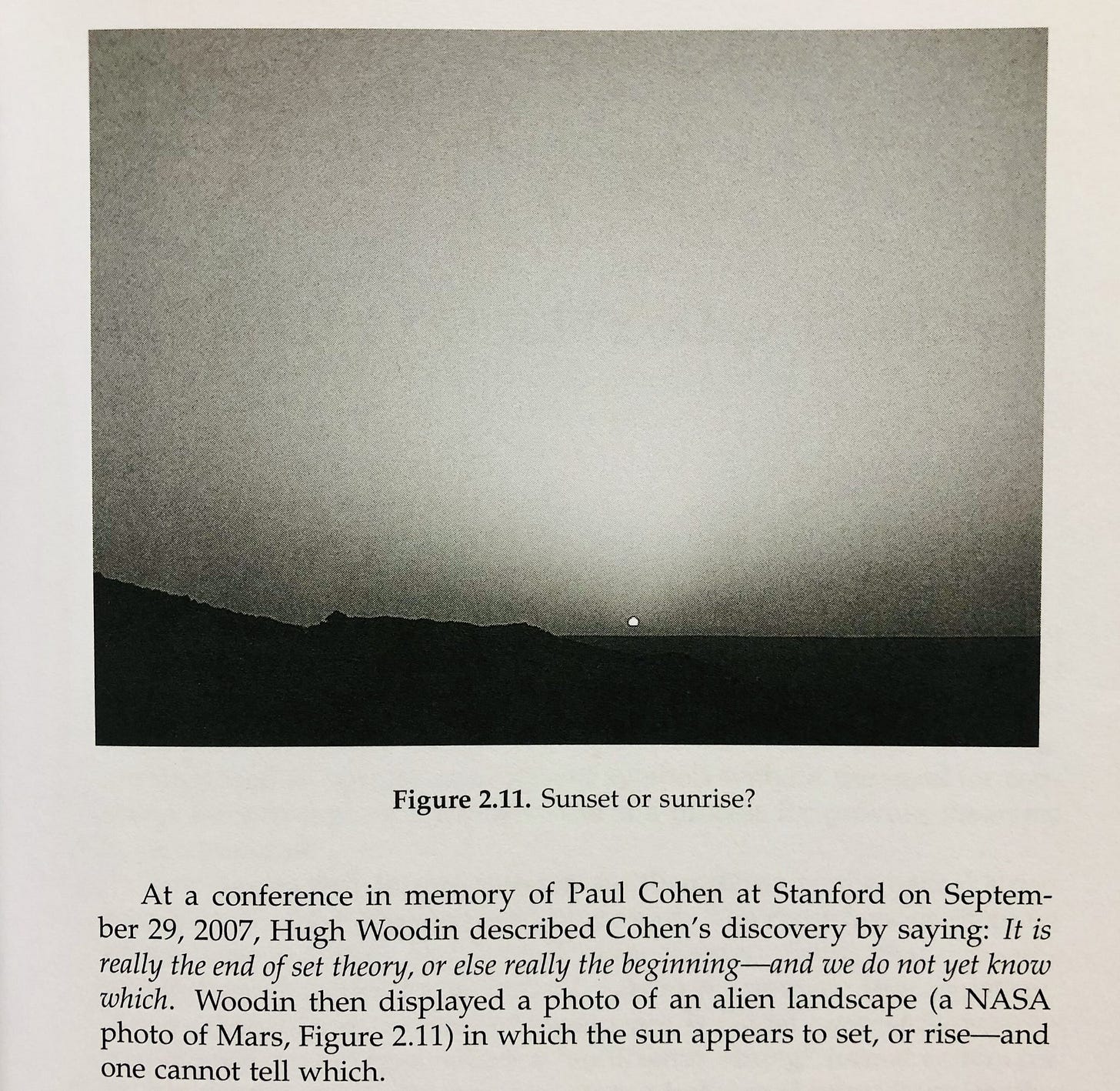

The above is a page from John Stillwell’s Roads to Infinity where Hugh Woodin is reported asking the question of the potential end of set theory next to a NASA photo of Mars in which rise and set are indistinguishable.9 Sunrise or sunset of the unsetly? Woodin, speaking in 2007, here makes in advance the central point of Ruda’s meta-logic of exposing set theory to its own end. In the end, Ruda says, the ends of set theory may be the most infinite points, the points at which we can say that the end of the end of set theory is the end of the end of set theory, and this, we can add, is itself a silently sexual logic.10 Woodin plays an ambiguous role in The Immanence of Truths, with Badiou finding it necessary to reject the more skeptical mode of his later work, which is effectively kept outside the frame.11 More reading might be be done on this point, but for now let’s note one thing Woodin says in this later more questioning mode:

So that’s where we are. To me set theory is at a tipping point. (That’s another English phrase.) We don’t know which way it’s gonna tip, and which way it tips depends upon this conjecture. It may tip into light, the conjecture is true, and now we can really get started in set theory. The problem with set theory is it’s very hard to do mathematics when every problem is unsolvable. How can you build a framework of set theory when every set theorem . . . it’s not just CH that is unsolvable . . . many set theorems are . . . you can’t get started . . . you just can’t get started. . . . So set theory’s never had a chance. V = ultimate L removes all that. The only ambiguity is the size, but that’s okay. So what’s the other way it could go? It could tip into darkness. It could tip into chaos, and that is, this conjecture’s false, the universality theorem is the precursor to where this line of investigation ends.

Tipping point of the sunrise and sunset.

*

The truth-event of sex is also to be found in the work of Paul Celan, in terms of arising generation out of what he calls ‘angel-matter’, and how this links to sustain. The desire to fuck, to make love, brings me into direct contact with sex as an infinite test drive and testing, of the matter of infinity itself, written out as end without end.12 We find Celan saying something with a very similar form in a 1952 letter to his wife Gisèle Lestrange: ‘Maïa, my love, I would like to be able to tell you how much I want all this to remain, to remain for us, to remain for us forever’, which may also be translated as, ‘Maïa, my love, I wish I could tell you how much I want all this to stay, stay for us, stay for ever’. I would like all this, all this this here, to remain forever, you and I and everyone, infinitely here and embraced, this is what I would like to be able to tell you, and this in a sense is angel-matter itself, taking place not as the metaphysical being an individual angel or the psyche of an angel might have, infinitely generative, but as something else, something infinitely threatened, newly written out, soothing, a gentle sexual difference. The upward thrust of angelic matter is itself sexually bestowed, phallangelically, as Pierre Joris has it:

OUT OF ANGEL-MATTER, on the day

of the ensouling, phallically

united in the One

—He, the Enlivening-Just, slept you toward me,

sister—, upward

streaming through the channels, up into the rootcrown:

parted

she hoists us up, equal-eternal,

with standing brain, a bolt of lightning

sews our skulls aright, the pans

and all

the still-to-be-dissemened bones . . . Throughout his hundreds of poems, Celan meditates on what it means to be a ‘standing brain’, to stand, to stand up, to resist, to stand inside you, to be alert there, or soft, to be phallically united in the One, a one without angel, a one open to the end of infinity, a scattered-One (‘dissemened’), not the one set aside in Badiou’s ontological decision, not quite, but another one to that one, a meta-forced eros, a meta-forcical sexual ooze, an unsetly 滲み出るエロ, sexual bigness and standing and panning as a meta-ontological proof of form and form of proof.13 The sexual absolute, if there is one, may be said to be the ‘X’ that marks the spot where crosses the absolutely fucking infinite (the ‘oh my god’ of the best fuck in the world) and the terror of death as absolutely certain, inscribed and experienced for example by Orange who was shot and bled profusely in the back seat of a car driven by White at the beginning of Reservoir Dogs (‘All this blood is scaring the shit out of me. I’m gonna die, I know it.’)—‘oh god’ being the first barely audible words out of Orange’s mouth, the only ones expressive of mortal pain. Fucking—the act and the word—finitizes as much as it absolutizes but without in a sense leaving a waste-product (déchet) entirely outside, reminding us of the ‘absolute almost-being’, the almost huge that Adjani experiences at the end of Possession (1981). Remember how Mark discovers (walks in on) Anna having sex with the creature as she cries ‘Almost!’ over and over again.

In his final seminars, Derrida writes, following the logic and writing of différance:

The infinite makes itself finite, it comes to an end [l’infini se finit].

The coming to an end of that which can’t come to an end, but might, was this ever anything but sex as a type of incredible proof of life, as a meta-phenomenology of the end of the absolute? This, right here, is the experience of the contemporary subject, as well as its empirical hell and chance. That which can never come to an end precisely because the infinite cannot, ends. The infinite finitizes itself—and only this is its (infinite) chance. The infinite finishes. The infinite, like sex in all its ambiguity, is that which makes of itself the finite thing—this finite thing. But these last statements would be the whole story of a writing of the infinite only if we remain within the dialectical thinking it is the very point of this writing to deconstruct and render unstable, and only if the reader misunderstands différance as (dialectical) difference, as if there were no difference at all between différance and difference. It is not after all that the infinite is finite, as Ruda and Badiou almost end up making the mistake of saying, or that infinite différance is to be sublated by a dialectical machine we always assume is easy to read and well-known (‘Hegel’); rather, what is the case is that the finish of the unfinishable infinite is itself subject to an (infinitely finite and finitely infinite) set of different dimensions of linguistic translation. For example, the infinite is that which finitizes itself, and just that is what makes it so infinite—more than infinite in fact. The infinite can only be infinite (more than infinite) starting from its infinitely scattered (dimensional) finitude that gathers itself at no one point, and this is why Geoffrey Bennington is ultimately moved to formulate something as complex-sounding as ‘the (nondialectical) difference (or différance) between différance and (dialectical) difference’.14 To keep on going, the infinite is that which infinitizes itself, and just that is what makes it so finite—more than finite in fact. The infinite can only be more, both more than infinite and more than finite. The infinitely finite becoming-infinite of the finite subjected to the perhaps of an end according to many dimensions of thought that scatter just is infinite end, infinite sex, portending and containing resistance to the end thought and curled up in the body as the experience of ‘equal-eternal’, and ‘rootcrown’, of ‘still-to-be-dissemened bones’.

Frank Ruda, ‘To The End: Exposing the Absolute’ (2020), pp. 317-318.

Ibid., pp. 334-336.

Alain Badiou, The Immanence of Truths (2022), p. 389.

Ibid., p. 328.

‘To The End’, p. 339.

Ibid., p. 329 n. 59.

Ibid., p. 428-429.

Jacques Derrida, ‘The Notion of the World’ (2024 [1961]), p. 125.

John Stillwell, Roads to Infinity (2010), p. 65.

For the complex logic of ‘the end of the end’ see above all Geoffrey Bennington, Kant on the Frontier (2017).

The Immanence of Truths, p. 68. Badiou writes, somewhat tellingly, ‘Honesty compels me to say that, since the end of the last century, Woodin—like Cohen in his day—seems to have become more cautious regarding the absolute . . .’ (ellipsis Badiou’s own).

The Immanence of Truths, p. 441: ‘That said, his proof leaves the ontological theory of infinities in the complicated situation of having to end without ending.’ And on p. 434, just before the rare reference to Derrida: ‘It is as if the absolute imposed a sort of closed openness on the ascending hierarchy of infinities.’

Celan’s ‘Aus Engelsmaterie’ | ‘Out of angel-matter’ is taken from the volume Threadsuns and is untranslatably translated by Joris in Breathturn into Timestead (2014), p. 193.

Geoffrey Bennington, Scatter 2 (2021), p. 300.