THE END OF THE UNIVERSE, PART XVIII: DURAS THE ALCOHOLIC, DOING NOTHING, AND 'RELAPSE'

Duras the alcoholic. How soon is nothing. How soon is the decision to do nothing. How old are 'the children'? Is it possible to impossibilize relapse?

DOING NOTHING

In the last part of this series—which is an ongoing written seminar running parallel to the irl one about to start in NYC—Marguerite Duras was mentioned and her comments about doing nothing. Let’s turn what she said into another reading prompt or cue:

I want to make everything about nothing but I don’t know how.

Or:

If I were strong enough to do nothing, I would do nothing.

But why do nothing? Let’s say that what’s good about doing nothing is that I get to do it in time. Doing nothing quickly allows everything in time. Which is to say in good time.

It’s as if one says: I want to turn around and walk into reality and watch the end of the world happen in a state of incredible sobriety but I don’t know how. I want to open myself to nothing, to material reality at and as a possible end of time, but I don’t know how. I want to face the end of the world but I feel too much pain. The end of the world takes vulnerability; it means unbearable compassion and suffering.

Now, if we wanted to learn something wouldn’t that be it?

Wouldn’t we want to learn what Duras couldn’t learn, and to do so in good time? That is, to learn according to the rhythms of the good? What would be good is being here at the end of the world to see it. What would be good is being here at the end of the world to see the end of the world.1

What could be better than being there to see it happen?

(What good is the good if we can’t be here to do this one thing now?)

Let’s therefore try this:

The Good is being there in Good time.

Or let’s go further and say to ourselves:

I want to be there in good time to see that everything is about nothing, including ‘the end of the world’.

BUT WHAT DID DURAS ACTUALLY SAY?

What Duras actually said was in relation to cinema but we can dispense with that as incidental. Her statement serves well for any preoccupation, concern or muse. Here is what she said:

I make films to fill my time. If I had the strength to do nothing, I would do nothing. It is only because I haven’t the strength to do nothing that I make films. For no other reason. This is the truest thing I can say about my practice.

The inability to do nothing is what she is talking about. The reading cue version of what she said is, simply:

If I had the strength to do nothing, I would do nothing.

Or:

I don’t have the strength to do nothing.

What kind of strength does it take to do this kind of nothing that Duras couldn’t bring herself to do? And, perhaps even more importantly, how does this relate to addiction and to knowing that she herself was a relapsing alcoholic till the very end of her life?

We can proliferate these questions, as if on a whiteboard, and say:

Can you teach nothing? Can you believe in doing nothing without making a case for nothing? Can you believe in the good without making a case for the good? Can we form a syllabus for doing nothing? For the practice of nothing? How does film teach? Does it? Is posting anything and was it worth it? Can you believe in what is without making a case for what is? Is there nothing to learn? What does it take to give up in time?

The apparent mastery of artists and their works can be delimited when we know who they are and exactly what their lives are like. When we know Duras was an alcoholic and that her genius was punctuated by hospital stays and psychotic frenzies, then we start to see the masterpieces as moments of relapse in every sense of that word. But these are not just relatively innocent ‘relapses’, they are relapses away from doing nothing, and we have decided to define doing nothing for now—in this context—as the Good.

DURAS THE ALCOHOLIC

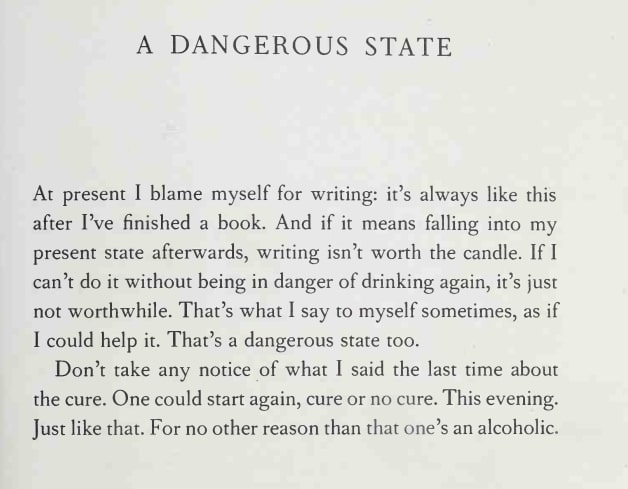

In her book of written-up interviews called Practicalities, with Jérôme Beaujour, we can find a late text by Duras called ‘A Dangerous State’ that is about the dangerous state of relapse in general. Here is the text exactly as it appears in English translation, as published in 1990.

At first ‘the present state’ is not explicitly named, it’s just ‘the present state’. After that it becomes clear ‘the present state’ is the relapse into drinking again. The immediate neural implication here is that art equates to an addictive regime that cannot be escaped once we enter the loop. To put it in other terms, we cannot practice nothing in art—or anything else for that matter—without beginning to make a case for it. The making of a case is itself the presence felt of an addictive regime (case, rhetoric, force, object, and so on).

Reading backwards as if in a relapse autopsy, we can therefore understand why Duras begins by blaming herself for writing, and why it’s ‘always’ like this after she has finished a book. It’s always like this, we might say, because writing a book or whatever the artistic practice is, is always the beginning of the slide back into an addictive regime. In a sense we can simply say,

writing is the relapse.

Or to be more specific for now:

writing is the relapse for Duras

and this ‘relapse’, she realizes, extends across cinema and writing, since for her writing and cinema were intimately involved as with no other director. Duras perhaps more than any other was in a position to know irreversibly that there was no point in her making films and writing since these are irreversible addictive regimes.

Let’s say this again by saying that Duras is confessing that writing isn’t made not worth it because it leads to drinking but because ‘the first drink’ (a literal metaphor) precedes writing of any kind. All that is left is the prospect of ‘incredible sobriety’—we will return to this quote—but this is too hard for her, because she isn’t strong enough to do nothing. The real reason she can’t do nothing is that she is caught inside addictogenesis (the broader addictive scope of plasticity).

INEVITABLE RELAPSE, THE TWO RELAPSES

In the end Duras is telling herself she will relapse before she does so, and we can say that this is a fatal problem for her art and in a way forces us to recognize that we can find very little there—except an irreversible statement of irreversible relapse as proved within the bio-genetic frame as itself captured by a broader addictogenesis.

The second relapse, she says, exists in thinking one can avoid the first through the simple act of abstinence. For her at least, the period of clarity and escape from addictogenesis that seems to be cinema or writing is simply an unsustainable gap or timeout away from that to which she will inevitably return. The ‘dangerous state’ she refers to is the admixture of these two modes of relapse.

The relapse of drinking again that means for her that, behind closed doors, writing has never been worth it, and therefore cannot be worth it for us either, however much we pretend otherwise.2

And the relapse particular to her of knowing that thinking she is abstinent from a ‘being Duras’ that involves inevitable relapse into addictogenesis is itself another ‘dangerous state’.

The text ‘A Dangerous State’ is therefore an extremely naked analysis of the inevitability of relapse for the creature or automaton that engages the act of creation.

THE CHILDREN

And yet, Duras admits that is it possible to do nothing, just that she herself is not strong enough for this. Nothing is possible but she cannot do it. She sees that it is possible but also knows the possibility of relapse away from Nothing as built-in.

Her final film The Children is about this very problem, and in some ways solves it. In order to do this, Duras makes what is perhaps her sole cinematic comedy. The quite frankly incredible—properly incredible—comedy here is that a character exists who has realized and acted on what Duras knew without being able to practice.

This character is Ernesto, and Ernesto is a large child who essentially decides to do nothing at an incredibly young age. He goes to school once and this is what is incredible. Once is enough for him to understand that it isn’t worth it.

In her final film, Duras hands over to this large child her own real position, the position of an absconding irreversible truant, admitting that all art is simply addictogenesis and nothing else. The comedy of The Children is Duras effacing herself in the direction of a child who knew better than her what to do. The mystery and mastery of ‘genius’ is nothing.

The incredible is knowing it’s not worth it at an incredibly young age. Yet, the comedy is knowing that ‘the children’ here are played as adults. In Ernesto’s case, the actor Axel Bogousslavsky makes no effort to pretend to be a child. Rather, it’s simply the case that it is incredible that he really is a child. The point is that the children in The Children are of any age, and, therefore, that the position of finding nothing worth it is pre-given. What makes The Children beautiful is this recognition that Duras had been wrong to think that relapse was inevitable.

DURAS ON SCHOOL

There is a complicated and comical—the very comedy of the film—ambiguity in The Children about whether Ernesto decides not to go to school because he doesn’t wish to be taught what he already knows or because he doesn’t wish to be taught what he doesn’t know (because only what he already knows is interesting). His Italo-Russian parents allow him to develop these thoughts and his exception which in turn affects the teacher and the whole system of the family, especially perhaps his relationship with his mother.

Ernesto implies that schools merely have the function of the abandonment of the mother, and therefore women in general. The child goes to school and the mother is abandoned and the child is abandoned. It is as if all children find school boring precisely because it condescends to them in teaching them either what they already know or what they don’t need to know; in other words it is as if boredom is The Real and not just some kind of pathological offshoot. The bored child actually understands what the school doesn’t.3 They want to be with their mother. The mother’s love is abandoned and subdued, and not, as it were, taught to the child, who needs to understand the maternal element, the pristine gynaecium, without which nothing is never anything and time runs out.

CINEMA

When it comes to cinema, Duras will admit, there too, that she should have just done nothing. She says this not so much in relation to the cinema she made but in relation to the cinema or rather film of her own life, the real film of what she chose to do. The real film, we can add, of what she chose to do with regard to nothing.4

Duras writes,

What might she have done differently? The answer is,

nothing.

As in,

I should have just stood there in front of the camera and done nothing.

Or,

I just wanted to do nothing, that’s all.

Or,

Isn’t nothing the Good?

The cinema in which we do nothing—a better life, now—is the one Duras tried—and even so failed—to make in The Children. As Mondina writes,

Cinema is an embarrassing millionaire. But what if it was low budget? What if it was just film?

The great point in life—the greatest of the great—becomes whether I can decide to do nothing or not and how soon. Cinema here is no longer the making of films. The making of films has been left behind because all that is simply another variation within the general addictive regime of aesthetics, what Paul de Man and Tom Cohen broadly index as the suicidal epistemology of tropes. The problem here isn’t that a film was badly made, it’s that the life accompanying a whole series of cinematic masterpieces was itself a badly made film. The real film—the film of her life—was not the films she made that succeeded—appeared to succeed—but something else.

The Angelicism Seminar will run from next month. See dissolution_seminar on ig for details.

Or even better, perhaps, what would be good is being here at the end of the world to find out that the end of the world is not. Which is to say, to find out that the end of the world is not the end of the world.

And perhaps what I am saying is this: we will go to absolutely any lengths at all to pretend otherwise.

What I mean is: Boredom points at incredible sobriety.

It’s only later on, she says, that we dare to say or write down these truths, or in a transcendental childhood that was present—and is present—all along.